The LOGBOOK

Welcome to The LOGBOOK, the section of the magazine for all those various bits of aviation history that don’t really fit in any other place. Here you will find short stories, hangar flying, bull sessions, along with preservation news, gate guards, museums, and just about anything else. In over 20 years of publication, we have a lot of stuff to post here. Additionally, new items will be posted on a regular basis, so check back often. Have a quick story to tell? Drop us a line. Note that the most recent posts are added on to the bottom of the page.

The following article was written by 2d Lt. Herbert L. Merillat, Marine Corps Public Relations Officer in the Solomon Islands.

It appeared in the 1 January 1943 issue of Naval Aviation News magazine:

Guadalcanal, Nov. 18 -- (Delayed)

Marine Crops ground crews on Henderson Field, working in mud and dust, under shellings and bombings, to keep the planes flying, have made possible the brilliant successes of our aviators here. Their tools are few, and some primitive. They have no elaborate machine shops or weatherproof buildings. They have little rest. Many of the tattered planes which they put back into the air would discourage less determined repair gangs. "The Book" on proper organization and methods for maintaining plans has long since been discarded. The men have improvised repairs, patches, stop-gaps that would make the book writers groan. They've worked miracles of repair which have spelled success for the others who defended this American toehold in the Solomons.

"We salvage everything but the bullet holes," said 2d Lt. George Cole, who since mid-October has been in charge of heavy repair work on Henderson Field.

"Take, for example, No. 117," he said. "She needs an engine change. Both elevators, both stabilizers, the right auxiliary gas tank, the right and center section flaps, the right aileron, windshield, rudder, both wheels, and brake assembly will have to be replaced by parts from other ships.”

“Then after some quick figuring she'll be in the air. What we used to do in six months we do here in six days. Here a motor is changed in two and a half to three hours. Back home we considered three days a fast change.

"Experience went all to hell in favor of hard work. We have taken kids who don't know anything about the work and after a little while they can produce. Before we thought they had to have long training.

"What makes it so enjoyable (what a word to describe work under such conditions) is the willingness of everyone to chip in and work in the midst of shells, bombs, and everything else.”

2d Lt. Morris K. Kurtz was in charge of repairing the Douglas dive bombers in the early days of Henderson Field. Marine Gunner Norman G. Henderson, who arrived in September to help supervise the work, is still on the job. 2d Lt. William L. Woodruff was engineering officer in charge of scout bomber repair work during the critical days of mid-October, when the Japs repeatedly shelled and bombed the airfield for three days and nights. For 72 hours the repair crews had no rest.

Lt Col. Albert D. Cooley, in charge of dive bomber operations, has called Lt. Woodruff the real hero of October 15, when dawn revealed Jap transports busily unloading within a few miles of the airfield. Under Woodruff's supervision, the ground crews had put many planes into commission by noon. They blasted the Jap transports.

1st Lt. Robert E. Wall is the new engineering officer in charge of dive bomber repair work. He is assisted by Marine Gunner Zachariah J. Brown.

Lt. Wall and Marine Gunner Brown took us around the bomb-pocked, shell-torn field to show us some of the miracles of repair work that have been done. Almost every plane bore a patch of some kind. Each dive bomber is inspected as it comes in from a flight. Shrapnel and bullet holes are quickly patched. "What we used to call a 'temporary patch usually outlasts the plane here," Brown said.

The rudder of one plane had been riddled by shrapnel from a Jap anti-aircraft gun. More than 50 patches had bern slapped on the rudder. The plane was ready to fly again even minutes after she landed. In truth, they don't seem to be discouraged by any repair job. They have kept the dive bombers in the air. Once in the air, the dive bombers and their pilots have proven many times what they can do.

This article appeared in the 1 Quarter 2024 digital issue of LOGBOOK magazine.

Preservation

George R. Hall Air Park

Hattiesburg, Mississippi

Located at the Bobby L. Chain Municipal Airport in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, the George R. Hall Air Park is named for Colonel George R, Hall, U.S. Air Force, and as the plaque states, is: “Dedicated in memory of all American Prisoners of War and those listed as Missing in Action in service to our Country’s Defense.”

A native of Hattiesburg, Colonel Hall pinned on his Air Force pilot’s wings in August 1954, and after various flying assignments, in May 1963, began flying reconnaissance missions over Vietnam for the 15th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron . On 27 September 1965, his McDonnell RF-101C Voodoo took ground fire while then Captain Hall was on a mission over North Vietnam, and he was forced to eject. He subsequently spent the next 2,695 days as a Prisoner of War. On 12 February 1973, as part of Operation Homecoming, he was finally released from captivity.Returning to flight status, he finished out his career as the Deputy Commander of Operations for the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Wing, flying the McDonnell RF-4C Phantom II. In 2005, retired Colonel Hall published a book about his experiences in Southeast Asia titled: Commitment to Honor, a Prisoner of War Remembers Vietnam. Colonel Hall passed away on 16 February 2014.

Developed in the mid-1980s. the George R. Hall Air Park displays three plinth-mounted jets (seen below) that would have been appropriate for Colonel Hall’s days in the Air Force, including an McDonnell RF-101C Voodoo - Serial Number (S/N) 56-217, a Lockheed T-33A Shooting Star (or T-Bird) S/N 52-9590, and a Republic RF-84F Thunderflash - S/N53-7636. All of the aircraft a very well cared for, and presented in fine condition.

This article appeared in the 2nd Quarter 2016 print issue of LOGBOOK magazine

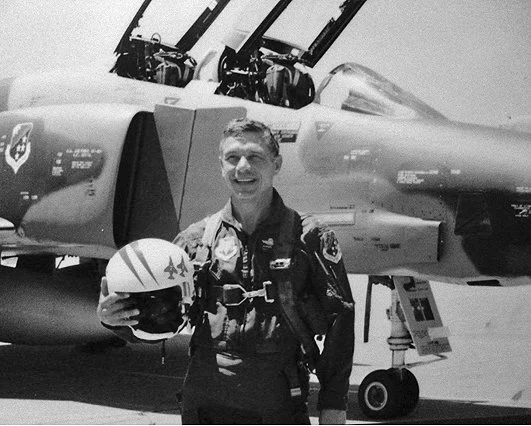

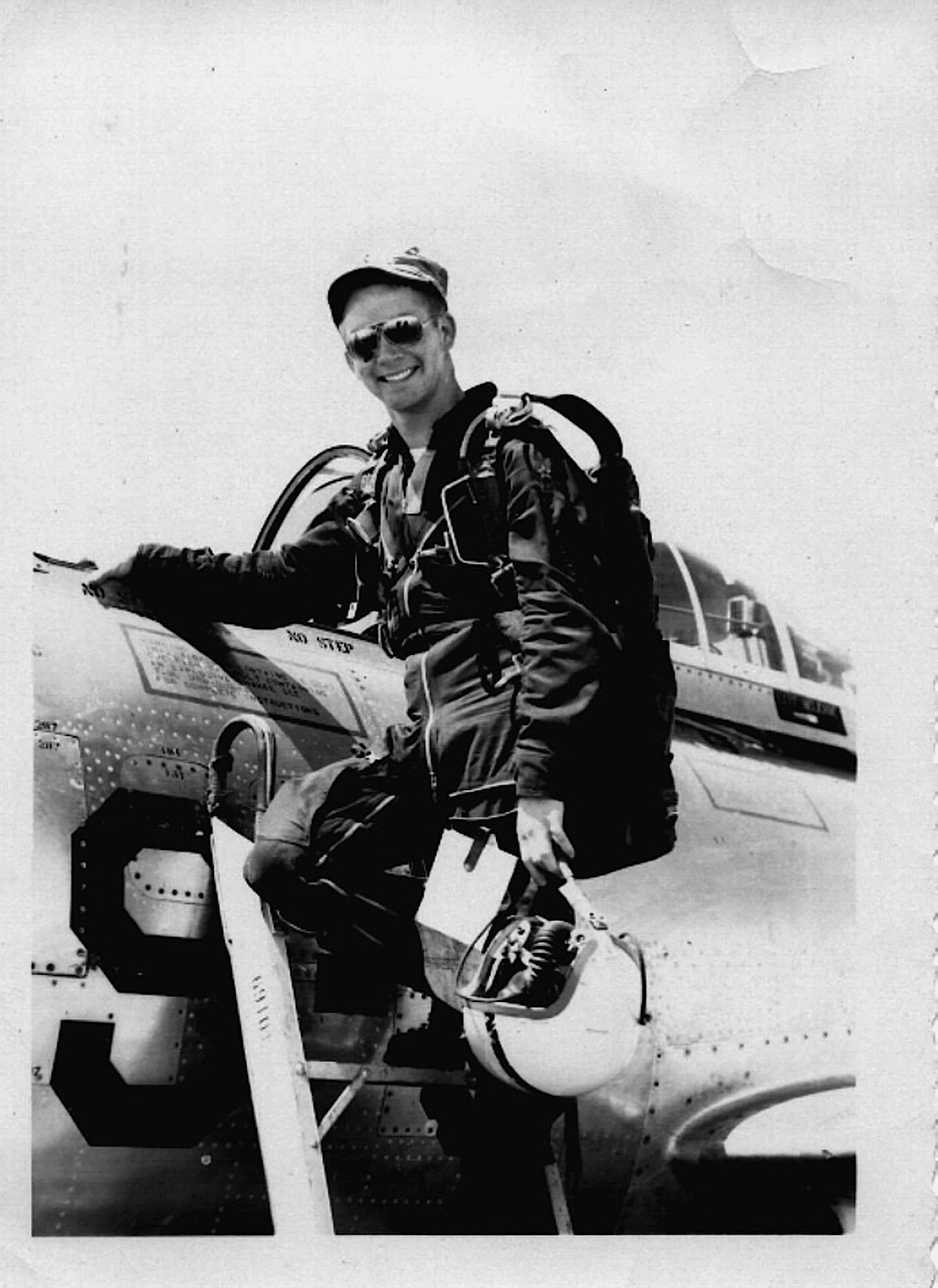

Later in his Air Force career, Colonel George R Hall stands in front of a McDonnell RF-4C Phantom II. Photo: U.S. Air Force

The Flying Resume of Ralph W. Ritchie

by

Dave Powers

In a previous issue of LOGBOOK magazine I introduced you to a man by the name of Ralph Westley Ritchie (see image below, when he was an officer in the Royal Air Force), who according to a couple of old magazine articles, supposedly lived a flying life that was more suitable to an adventure novel. Much of the information in the articles was a bit vague, and without much corroboration, so I decided to do some more research. Could what was presented in those old articles really be true? Well, the answer is actually “Yes,” well sort of.

Two avenues of research that I tapped were the military records folks, both the U.S. Navy and the Royal Air Force. The other day, the U.S Navy records arrived – all 500 pages of them. It will take a while to fully delve through these records, but I have found an interesting document that chronicles much of his life in the air. I am still awaiting the Royal Air Force records.

After World War Two, Ritchie reenlisted in the Navy. At the time he was not in a flying billet, rather, as a chief boatswain’s mate, he was working a series of ground jobs. A qualified pilot – an enlisted Naval Aviation Pilot – Ritchie made an application to get back into flying, and along with the official paperwork Ritchie included a resume of his flying experience. Presented here, in an unedited form, is that resume.

SUMMARY OF FLYING EXPERIENCE OF:

RITCHIE, RALPH WESTLEY, 183 60 25, CBM(AA) USN

1922 - Made application for course in photography at Naval Photographic School, Anacostia, D.C. During this course of instructions became interested in aviation as this course included aerial photography. Passed this course with mark of 4.0. Remained at Anacostia as station photographer, also at the Bureau of Aeronautics.

1923 - Made application for flight training and was sent to Pensacola, Florida to enter training in Class 18. Finished this course November 1923 mark 3.56. Was transferred to U.S.S. WRIGHT and attached to

VS-l. Made regular routine flights with this Squadron. At this time, squadron was equipped with F5L’s. After the Hawaiian Maneuvers 1925-1926, re-equipped with SC2’s. Remained in VS-1 and VT-1 until being

transferred to NAS Pensacola as Flight Instructor.

1927 - Instructor in practical flying at Pensacola Squadron #6 and #8, Land and Seaplanes. Carried students through total course. Qualified 22 lost 1.

1929 - Was transferred from Squadron #8 to photographic section as pilot. Summer of 1929 was transferred to U.S.S. LEXINGTON, VT-2. November 5, 1929 was discharged from U.S. Navy by reason of

Special Order (Own convenience).

1929-1930 - Flying for NyrBa Line. (New York, Rio and Buenos Aires Line), ferried new Consolidated flying boats P.B.Y. types, from factory (Buffalo, N.Y.) to divisions on Company line. After second trip was

made division superintendent Trinidad-Para. 1930 this company sold out to Pan-American Airways. Was taken over, by Pan-Air and flew between Miami and San Salvador, regular schedules first pilot.

October 1930 left Pan-Air due to excessive pilots and expiration of contract.

1931-1932 - Flew for TWA Transcontinental and Western Air. Flew between Newark, N.J. and Kansas City, Mo. Night mail (Northrop mail planes) and Ford Tri Motors Passengers mail and express.

1933 - Left TWA to make trip around world with Miss Aloha Wondwewell (Evylnn Hill). Spent 6 months in preparation for this flight which did not materialize due to lack of suitable aircraft for trip.

1934 - During this year flew as private pilot and owner of Charter plane and passenger flights. Newark N.J. or any place plane was charter to. Lost this aircraft in East River N.Y. at night due to fog.

(Stinson Reliant.)

1935-1936 - Was employed by Bol-Inca Mining Corporation flying a Sikorsky S-38. This job consisted of carrying freight from La Paz, Bolivia to the mine in the Kaka River. This river is situated in the interior

of Bolivia near the head waters of the Amazon. The airport at La Paz is 13,200 feet above sea level. The course led through a pass in the Andus at 15,500. Carried 1500 pounds of cargo per trip. These trips

were made daily (weather permitting) more than one per day. Flight was one hour and one half average. 1400 hours including ferrying plane to Bolivia.

1937 - Bol-Inca ceased to operate and I flew for Floyd Aero-Boliviana as pilot and instructor on JV-52 (Hinie) regular airline work. Approximately 825 hours.

1938 - Left Bolivia and went to Peru (Lima) to fly for Faucett Airways. Remained with Faucett for one year averaging 75 to 80 hours per month. Regular airline schedules in Peru. Plane owner built. Something like single engine Stinson but larger.

1939 - Returned to Bol-Inca to fly S-38 again. In June this year S-38 was lost due to running over a rapids in the river and tearing out bottom. At this time, took over flying duties for Avamya Mines using Tri Motor Ford. Used same airport (La Paz) but landed in valley by mine on one way strip, 600 meters. Finished contract with Aromya and returned to United States. Flew for Mr. Gordon Barbour as private pilot until May 1940. Mr. Barbour was Vice President of Bol-Inca.

1940 - Bought another S-38 from Pan-Air and flew it to Bolivia by way of Cuba, Mexico, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Columbia, Equidor, Peru and Chile. Finished other contract for Bol-Inca, returned again to Peru with Faucett. Met quite a few English in Peru and Bolivia and decided to join Royal Air Force.

1941 - Left Lima, Peru for London to Join RAF. Arrived in London in April and was commissioned in RAF after a course on British aircraft, was sent to a squadron and maintenance as test pilot. I remained on these duties until July 1941 when I was sent to Africa as test and ferry pilot. Made some trips from England to Gibraltar with long range bombers. While in Africa was convoy leader. These duties consisted of leading a convoy of aircraft from Takarodi, West Africa to squadrons in Egypt and Western Desert. Convoys ranged from 8 to 20 planes. Route 3,600 miles.

1943 - Left convoy duties and was attached to AirSeaRescue, Western Desert. These duties consisted of locating un-luckies shot down and remaining over them until they were rescued by surface craft. Squadron was credited with 207 rescues. Planes used were Wellington Bombers (land planes). After duties in Western desert went to Iran and Persian gulf to organize AirSea Rescue. Operated between Basra and Karachi, India.

1944 - After short tour of duty as Commanding Officer at Wadi-Haifa, Anglo Egyptian Sudan, returned to England and was released from RAF. Remained in London one month and re-enlisted in U.S. Navy, December 4, 1944. Was sent to Paris as Chief MAA on Admiral Kirks staff. Was then sent to Plymouth, England at Amphibious Base until June 1945. Returned to United States. (Five years away). Was discharged on points at P.S.C. Minneapolis on October 15, 1945. Re-enlisted January 5, 1946.

All these statements are true and may be verified through companies and air forces which employed me. I have flown a total of over 10,000 hours during my aviation career.

Ralph Westley Ritchie.

CBM, U. S. Navy.

Some Analysis: Well, there you have it. Except for his civilian flying, most of the above is corroborated by other official documents that came in the package. From his original enlistment in 1914, up through 1929, when he left the Navy for the first time, his service life is pretty well verified, and runs closely to the above narrative. He was a Naval Aviation Pilot and a flight instructor, as well as being the All-Navy heavyweight boxing champion and on the All-Navy football team.

His civilian flying life, starting in late 1929, while not wholly documented in the Navy documents, does at least have a ring of truth to it. Various non-Navy sources do corroborate his work at New York, Rio and Buenos Aires (NYRBA) Line, and while not so well established, his move to Pan American in 1930 is a reasonable transition. A few vestigial sources do indicate that a Ralph Ritchie flew for TWA, and his narrative tends to confirm this.

One interesting interlude in his flying career took place in 1933. Ritchie notes that he left TWA to assist a “Miss Aloha Wondwewell” on her round-the-world flight. To tell you the truth, I had to do a little research on this. Turns out that Aloha Wondwewell was born in 1906, as Idris Hall. In 1922, still only 16 years old, she joined an automobile racing team head by Valerian Johannes Pieczynski, who went by the name Walter Wanderwell. The race was a round-the-world driving contest between two Ford Model T-equipped teams. By the end of the race, she had adopted the name Aloha Wanderwell, eventually marrying Walter in 1925. For the next several years, Aloha developed her career as a professional explorer, photographer and film maker, lecturer and author. Legends abound about her life, everything from being held prisoner in China to joining and fighting for the French Foreign Legion. In 1932, her explorer husband, who some thought was an international spy, was murdered in California, a crime that was never solved. Later in 1932, after Walter’s murder, she learned how to fly, and made a trip to Brasil in search of lost explorer Percy Fawcett. During this expedition she crashed and was forced to live several months with jungle natives before being rescued. I really did not find too much about her planned round-the-world flight, to be assisted by Ritchie. Certainly, given her life up to 1933, a trip of this type was well within the realm of possibility. Perhaps the airplane she crashed in South America was the one that she was going to use on her round-the-world flight. Well, maybe.

As for Ritchie’s adventures in South America we only have his narrative to go by, but there are a few connections with historical records. The Bol-Inca Mining concern, owned by NYRBA founder Ralph O’Neill, did have a small fleet of Sikorsky S-38 amphibians. The airline Lloyd Aereo (not Floyd Aero) Boliviano did operate a small fleet of Junkers Ju-52 (not JV-52) Tri-Motors. By the why, Ritchie’s used the word “Hinie” in his narrative, which was a then quite popular, but highly derogatory, reference to Germany, particularly German soldiers.

In 1938 Faucett Airways – Compania de Aviacion Faucett, which was founded in 1928, by an American named Elmer J “Slim” Faucett, did operate a number of locally designed and built single engine transports known variously as Faucett-Stinson F.19s. Elmer Stinson had obtained the rights to build Stinson monoplanes in Lima, and with the help of Gale Alexander, a Stinson engineer, modified the original design to optimize it for high altitude work. The aircraft was quite popular in the region, and over 30 examples were built. This could be the “Plane owner built” mentioned in Ritchie’s narrative.

Further Navy documents do relate Ritchie’s induction into the Royal Air Force, however this consists mostly of the inclusive dates, not his actual service record. I will have to wait for the Royal Air Force records to get a better handle on his flying in Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

Unfortunately his post-war application to return to a flying billet in the U.S. Navy was denied, the document noting that there was an over abundance of both Naval Aviators and Naval Aviation Pilots. This was during the drastic post war demobilization, so it stands to reason that flying billets were becoming more and more scarce. Ritchie did remain in the Navy, as an Aviation Boatswain’s Mate and an Aviation Mechanist’s Mate, before retiring in 1950. He passed away in 1967, in Tampa, Florida.

If anyone out there has any clues on Ritchie’s rather eventful life, please feel free to drop me a line.

This article originally appeared on the 2nd Quarter 2016 print issue of LOGBOOK magazine.

The Origin of The Happy Hooligans

Possibly no other Air National Guard (ANG) unit has a nickname as well known as the “Happy Hooligans.” Where did that nickname come from?

The North Dakota Air National Guard’s 178th Fighter Squadron (FS) commander in the mid 1950s was Major Duane S. Larson ( later Brigadier General, Retired). Because of his

fatherly instincts, Major Larson became known as “Pappy” to his entire squadron. His men were dubbed “Hooligans” for their mischievous antics. Locally, they became known

as “Pappy and his Hooligans.” Because of Major Larson’s striking resemblance to the Steve Canyon comic strip character named “Happy Easter,” the squadron was soon

known as “Happy and his Hooligans,” and later shortened to the “Happy Hooligans” (around 1958). Soon everyone around the base was using the nickname “Happy Hooligans”

to describe the squadron.

According to unit lore, the name really took hold because of events at a 1950s summer camp at Volk Field, located near Camp Douglas, Wisconsin. Legend has it the 178th FS

had to march on the ramp to make up for the late night shenanigans of throwing all the “brass” out of bed after the club closed for the night. While marching on the ramp

the next day, with “Pappy” Larson, their 178th FS commander at their side, the 119th Fighter Group Commander, Lieutenant Colonel Marsh Johnson, called the squadron a

bunch of Hooligans, to which someone answered, “we might be Hooligans but we are happy Hooligans.”

In the early 1960’s, the North Dakota Air National Guard was searching for a motto to set them apart from other units. A contest was held to choose an official nickname;

no names received topped “Happy Hooligans,” so it was officially adopted as the unit’s nickname. In 1964, during the ANG Rick’s Trophy competition, “Happy Hooligans” was

painted on the unit’s Northrop F-89J Scorpion aircraft. This was the first time it appeared on the aircraft, but since then, each North Dakota ANG aircraft has carried that motto/logo prominently displayed on the tail.

Article courtesy of the 119th Wing, North Dakota Air National Guard. For more information, log on to: https://www.119wg.ang.af.mil

Above: Receiving federal recognition on 16 January 1947, the 178th Fighter Squadron (SE) was first equipped with the North American Aviation P-51D Mustang. The jet era began in June 1954, when the Mustangs were traded in for Lockheed F-94A/B Starfires, and the unit became a Fighter Interceptor Squadron. Photo: North Dakota Air National Guard

Below: A McDonnell F-4D-26-MC Phantom II - SN 64-965 - assigned to the “Happy Hooligans” of the North Dakota Air National Guard. The 178th flew the Phantom II from 1977 through 1990, back when the squadron was designated the 178th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, part of the 119th Fighter Interceptor Wing. This photo was taken during the USAF Air-To-Air Fighter Weapons Meet - “WILLIAM TELL ‘84.” In 1990, the squadron transitioned to the General Dynamics (now Lockheed Martin) F-16A Fighting Falcon. Today, the 178th Attack Squadron, 119th Wing, operates the General Atomics Aeronautical Systems MQ-9 Reaper. Photo: USAF by Staff Sergeant David Cornwell

This article originally appeared in the 1st Quarter 2021 print issue of LOGBOOK magazine

A Fine Gator Farewell

by

Garnett W. Haubelt

It was the summer of ‘75 at Naval Air Station (NAS) Miramar - FIGHTERTOWN, USA, and home to “The Eyes of the Fleet” - Detachment Three of Light Photographic Squadron SIXTY-THREE (VFP-63). We were on a shore tour, or on one of our infamous 72 hour standby cruises, when the squadron got a call from the Executive Officer (XO) of NAS Chase Field, in Beeville, Texas. Commander Bob Crowl was asking around if there was any way to have a static display of an F-8 Crusader at Beeville for the retirement ceremony of the Base Commanding Officer (CO), Captain Robert E. Ferguson. “Fergie” Ferguson, who flew the Crusader with Fighter Squadron ONE-TWO-FOUR (VF-124), as the Operations Officer, from 1959 to 1963, then with Fighter Squadron FIFTY-ONE (VF-51), as XO then CO, from 1965 to 1967, and then as the commander of Carrier Air Wing FIVE (CVW-5) as “CAG-5” in 1967. A static display would be really befitting as Captain Ferguson had commented to his XO that a “Crusader Farewell would be nice!” The task was turned over to Det. Three for implementation of this fitting farewell. Captain Ferguson was transitioning from a fine military career of over 32 years of Naval Service to his country to that of civilian life. The decision was made whereby not only a static display was a great compliment for such a great career, but a fly-by in burner would be even better. If a fly-by in burner was better, what would a section fly-by going “gates*” at the same time be like! Crusader Drivers don’t just “do” something unless it’s done “right,” so the mission was on.

Myself and wingman Commander John Peck - retired, and one of the last Gator

Drivers of Light Photographic Squadron THREE-ZERO-SIX (VFP 306) - set about to

accomplish the mission. Manning our Crusaders for our trip from Gunfighter Land

to Training Land was the start of a mission that has been firmly burned into my

aging brain. It so happened that the Big Man in the sky was looking favorable on the

day and provided the best of weather …. relative cool - for a Southern Texas August

day, calm and not a cloud in the sky. Things were planned, or more than likely luck

had its way, from the time of being handed off from Center to NAS Chase Field tower,

to the fly-by and to the landing. Upon check-in with TWR, from about 75 miles out

and 39,000 feet, we requested a high speed, low fly-by. XO Crowl had laid the ground

work as the pattern was cleared and permission was granted. Little did the TWR know

what we meant by high speed, low fly-by! Passing the lead, we started down hill

hoping to make an appearance sometime close to Fergie giving up his command and

career. Again the gods of aviation were smiling. Arriving at the northwest boundary of

the field somewhere between the hangar and Runway 13L, we were in super tight

formation, smoking at 550+ knots, cooler doors open, and somewhere between the

ground and the top of the hangar. I knew John had us in the weeds as I remember

looking through his lead and level at the top of the hangar. The hanger doors hand

been cracked open by about 10 to 20 feet - we were later told it was more for audio

effect than cooling - and as we went to MIL power and lit the burners that wonderful sound erupted from our two chariots of fire. There is nothing quite like the sound of a [Pratt & Whitney]

J-57 P 420 turbojet going into burner at warp speed ….. much less two of them at eyeball level. You can imagine the effect we had, especially when it all happened at the moment

Captain Ferguson’s foot stepped on the pavement as he was coming down the gangplank ….. going from military life to that of civilian.

Commander Crowl surly received the “last mission accomplished” award by making this great flyby a possibility …. starting with searching for the Crusaders to clearing the pattern for his CO.

“By the completion of the beautiful, precise, finale I must admit that I was in complete meltdown. The total surprise, exact precision and timing of the flyby as I departed the ceremony was the

final frosting on the cake. I had no idea there would be an F-8 flyby so the surprise was complete. It is, to this day, one of my most vivid, treasured memories,” were some of Fergie’s subsequent

remarks about the honor we had the pleasure of bestowing upon him. So much so, that by the time we had pulled up and came around for the break, doing either a “fan” or “tuck under” break -

can’t remember which … if either, landed, taxied to the Operations tarmac and shut down, Fergie’s replacement, Captain “Red” Issacks, who in his own right was a first class Landing Signal Officer

(LSO) and a MiG Master, met us with 4 beers in hand ….. one for each of ours, even before our feet could hit the tarmac! “By orders of the retiring CO,” we were told! Nothing could keep Captain Issacks from whisking us away to the reception, as it was his command , as well as the “command” of Fergie to be in attendance in order to receive the proper “Thank you from the bottom of my heart!” Can’t remember how many hands I shook that afternoon after being introduced as “These are the Gator Drivers that made my day!” Here it was, his special day but the Old Salt of a MiG Master Captain showered us young pup Lieutenants with more congratulations and “attaboys” than we were due! It’s stuff like this that warms the heart, at least mine and one retired Navy Captain!

It is truly amazing how the 1,929 Crusader Drivers (give or take a few) who flew the 1,219 F-8 Crusaders that were manufactured by the Chance Vought Company (again give or take a few) could experience the same feeling for this trusty ole bird - whether you flew it during the 50s, 60s, 70s or in it’s retirement years of the 80s & 90s.

F-8s Forever

Garnett W. “Hubie” Haubelt.

* Gates: “Going Gates” - into afterburner, accompanied by a loud bang as the 'burner lit. In the F-8 you ran the throttle forward to the stop and then moved it outward to ignite the afterburner. The F-8 Crusader did not have a modulated ’burner like modern aircraft. You were either in ’burner or out of ’burner.

This article originally appeared in the 1st Quarter 2021 print issue of LOGBOOK magazine.

A file photo of a Vought (LTV) RF-8G Crusader - a Photo-Crusader - assigned to Detachment Three of Light Photographic Squadron SIXTY-THREE (VFP-63). At the time - the mid-1970s - Det. Three was attached to Carrier Air Wing THREE (CVW-3), then embarked aboard the USS Saratoga (CV-60). The Modex Number 600 would indicated that this was the Carrier Air Wing commander’s aircraft - CAG Three’s bird.

Photo: U.S. Navy

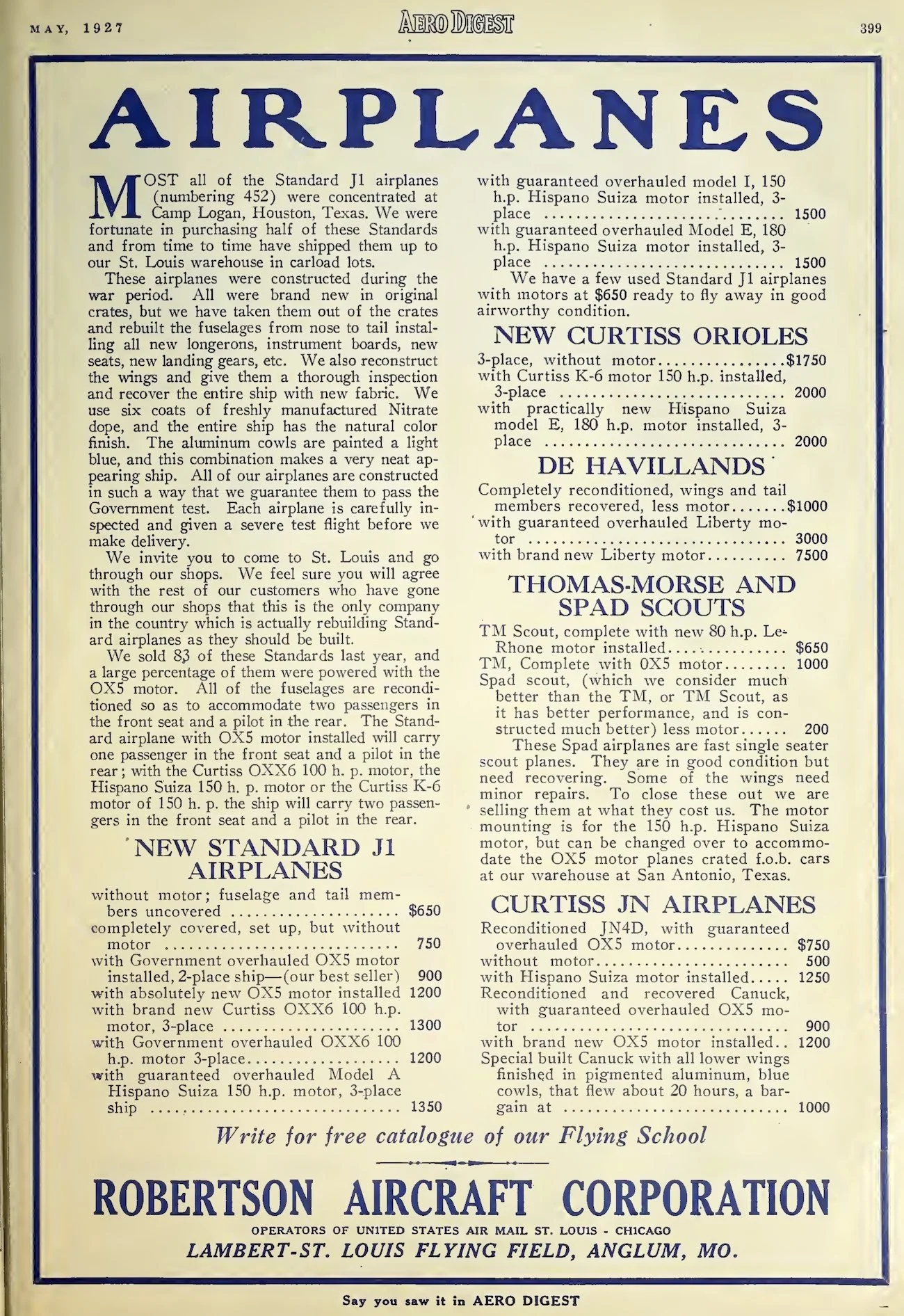

Some file photos of a few of the aircraft listed for sale in the Robertson Aircraft Corporation’s advertisement - May 1927, in Aero Digest.

Above: A Standard Aircraft Corporation J1 biplane. This restored example is in the collection of the National Museum of the USAF, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio. Photo: USAF

Left: Over the years, the Thomas-Morse Aircraft Corporation built a number of versions of their Scout, this one is an S-4B. The Scouts were all nicknamed “Tommys.” Photo: NARA

Below: A fine study of a Curtiss JN4D biplane, built by the Curtiss Aeroplane Company. Photo: NARA

This article was orignally published in the 1sr Quarter 2024 digital issue of LOGBOOK magazine.

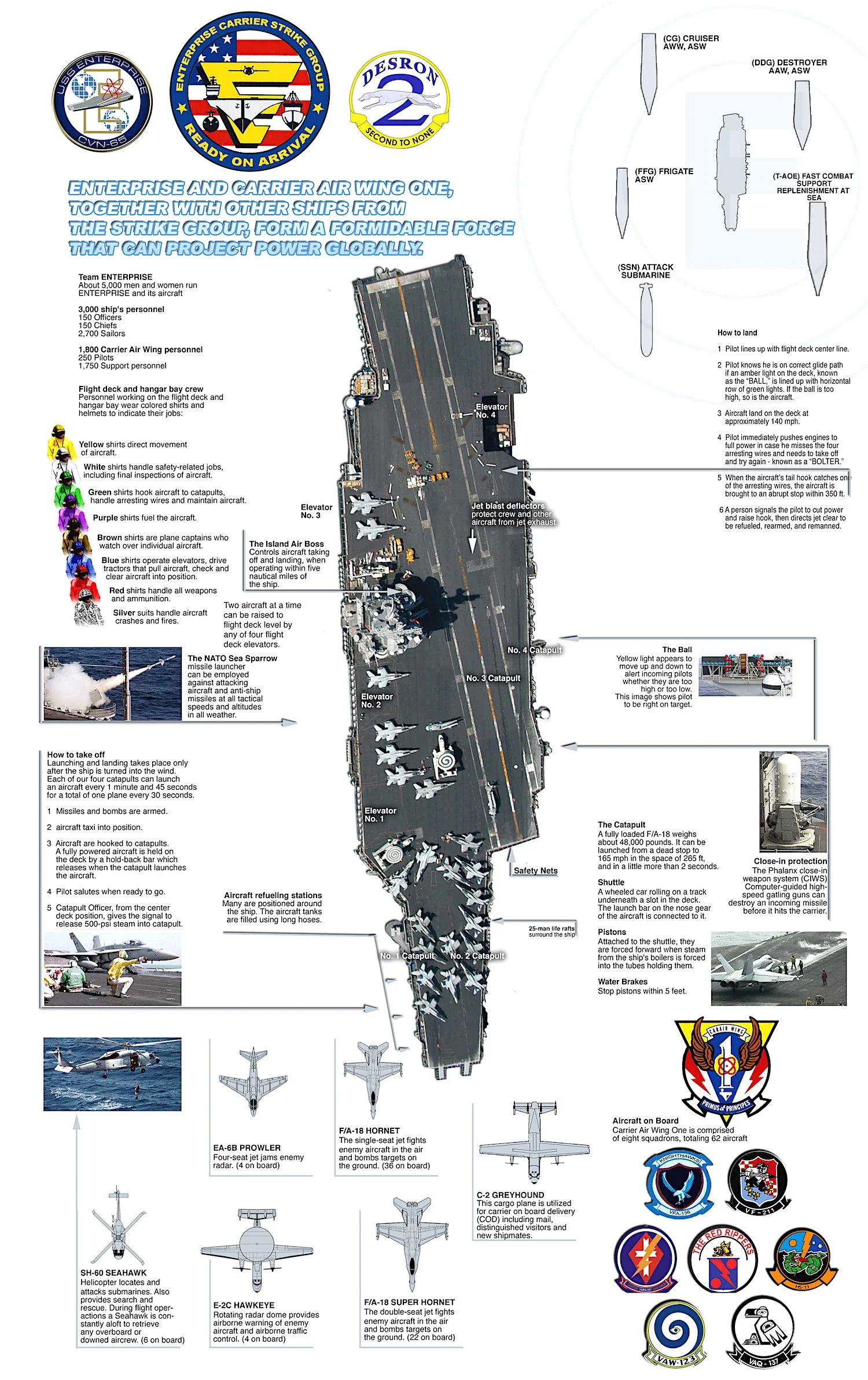

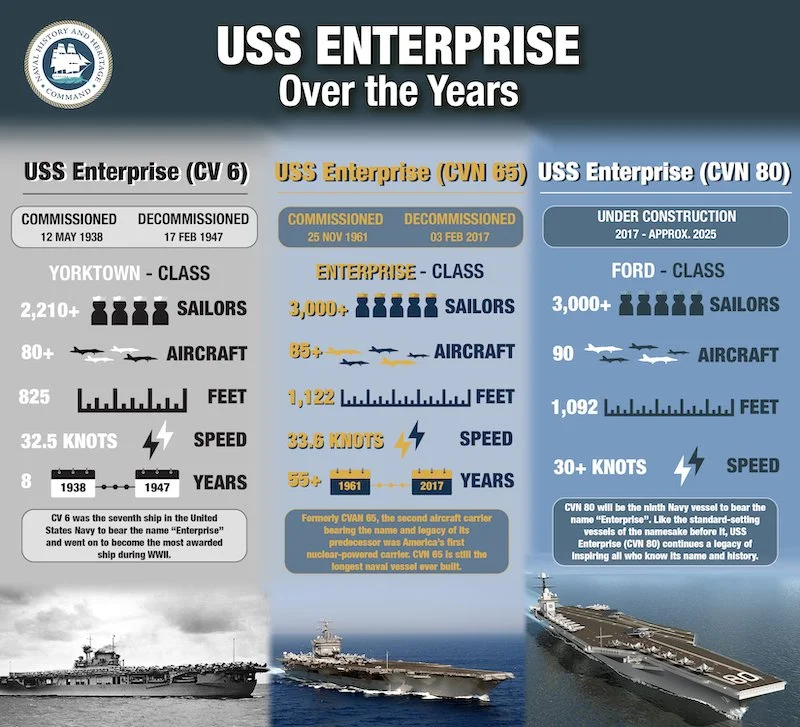

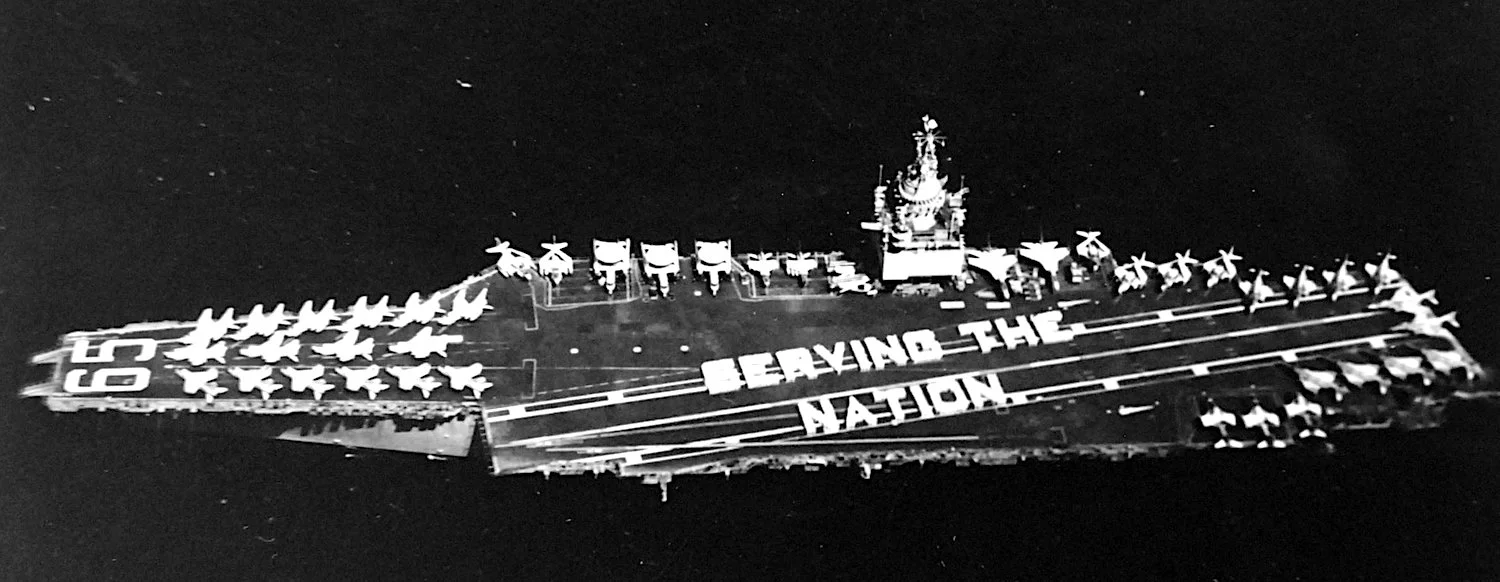

Above: The USS Enterprise (CVN-65) transits the Strait of Messina, 15 October 2012. Enterprise was deployed to the U.S. 6th Fleet area of responsibility conducting maritime security operations and theater security cooperation efforts. Photo: U.S. Navy by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Jeff Atherton

The USS Enterprise was placed in commission on 25 November 1961, designated as CVAN-65, at Newport News, Virginia. On 30 June 1975, the CVAN-65 designation was changed to CVN-65. Until the USS Nimitz (CVAN-68/CVN-68) came on line on 3 May 1975, Enterprise was the Navy’s only nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. The vessel was deactivated in 2012, and was struck from the Navy’s list on 3 February 2017.

Graphics: U.S. Navy via the Naval History and Heritage Command

This article originally appeared in the 3rd Quarter 2013 print issue of LOGBOOK.

USS Enterprise (CVAN-65), 1973. Crew of the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier and Attack Carrier Air Wing Fourteen form the words “Serving the Nation” on the flight deck. Photo: U.S. Navy by PH1 Ronald C. Bartel, May 19, 1973.

Haitian Nocturn

by

Jerry B. Driver

The year was 1984; I was flying as captain for Trans Air Link, a freight airline out of Miami. Our fleet consisted of ten Douglas DC-6s and one DC7. To the best of my

knowledge, the DC-7 was the last one flying in commercial airline service in the U.S. The full capabilities of both aircraft were not attainable due to the lack of 115/145 avgas.

In addition to the DC-7, we also operated another unique aircraft, an ex Sabena swing tail DC-6 freighter. This aircraft was loaded by swinging the tail section to the side

of the aircraft and using the open fuselage as a door. These aircraft were well maintained and the crews were well trained. Trans Air Link was one of the best of the piston

engined freight haulers of the day. We flew scheduled and non-scheduled flights throughout the Caribbean, and Central and South America. Trans Air Link also provided

contract flights for Zantop International Airlines from our northern base at Willow Run airport in Ypsilanti, Michigan.

During this time I was flying a schedule which included three round trips a week to Haiti. In 1984, the country was under the control of "Baby Doc" Duvalier. His

dictatorship was coming under increasing scrutiny from the outside world, and pressure was building internally for change. As a flight crew, we dealt primarily with the

business people involved with the freight we carried. Most of those were of the Creole caste. In Haiti, the Creoles were considered high society. Our relations with

the freight forwarders were very good. I found them to be easy to work with and pleasant to be around. They even taught me how to order "Jambon et Fromage," a

ham and cheese sandwich, from the café in the passenger terminal. The laborers who loaded and unloaded our aircraft were friendly and hard working. If you are familiar

with flight operations in the Caribbean, you will know that this was indeed an unusual situation.

We often overnighted in Port au Prince at the Holiday Inn. The food was good and the people were friendly. Sometimes, we stayed over the weekend and on occasion,

we would travel to Cap Haitian, and a resort in the mountains overlooking the ocean. At no time had we encountered any difficulties with the people of Haiti. But that was

soon to change.

We had heard of unrest in Haiti, but really did not see any overt indication of this during our stays in Port au Prince. We did notice, however, an increase in the

number of armed troops at the airport. These troops were a combination of regular Army and paramilitary police. I later learned that the Army troops had, for the most part,

no ammunition. The paramilitary police were said to have full ammo clips.

On a previous flight, while unloading some plate glass from the aircraft, several of the sheets of glass were dropped. The sound was similar to gunfire, and everyone on the tarmac hit the deck. Most of the soldiers followed our example, although a number were seen running away from the airport property. I also noticed that the police troops had turned their weapons towards the Army soldiers when the glass first broke. Once the cause of the alarm was discovered, things returned somewhat to normal, but with increased levels of tension.

Haiti was and continues to be one of the poorest nations in the world. Voodoo and magic are still practiced by some of the populace. In 1984, these practices were even more prevalent. "Baby Doc" Duvalier used these superstitions to further his despotic rule. Duvalier's secret police force, the Ton Ton Macoute, was famous for using Voodoo to intimidate its victims. I would soon meet the very embodiment of this feared group.

For many years, a small liberal arts college in the Midwest had maintained a campus in Haiti. American students had been there with no problems for several decades. The students came and went on the streets of Haiti, with little or no problem. Then suddenly, it all changed. A white, female, student was murdered while walking to market. Haiti went from a place where crews overnighted at the Port au Prince Holiday Inn to a quick turn around destination, and then we left. The Ton Ton Macoute was very much in evidence at the airport, and there was a feeling of unease among the Haitian workers. Even the Creole business owners were on edge. Both the U. S. State Department and the government of Haiti wanted to keep this story quiet. They both believed that the murder had political overtones.

My company was contacted and asked to return the girl's body to the United States. We were chosen because we loaded from the freight terminal which was some distance from the passenger terminal. Eastern was the primary passenger carrier to Haiti at the time. It was hoped that no one would notice the operations of an old DC-6 down at the end of the airport. I was contacted by officials from the American Consulate and arrangements were made for an escort to accompany the body back to the States. I also spoke with Haitian representatives in regards to when the body would arrive at the airport.

Our scheduled departure time was late afternoon, and as that time approached I noticed an increase in the number of soldiers around our loading area. Airport workers and spectators began to drift away from the freight area. The sky which had been clear most of the day had now turned a sullen gray with lightning visible in the distance. I had previously checked the weather and I knew we were heading towards a low over Cuba, with heavy thunderstorms forecast. I wanted to depart as soon as possible in order to avoid the worst of the weather.

As I waited for the young student's body to arrive for loading, I heard the wail of sirens approaching the freight ramp. I looked up to see a group of black sedans come onto the airport property. I did not see a hearse. The cars pulled up around the tail of my aircraft and a very tall, very black individual got out of the lead vehicle. Other paramilitary types got out of the remaining vehicles. As they took up positions around the aircraft, the tall man came over and announced himself as the commander of the Ton Ton Macoute. He said that the girl's body would arrive shortly. I noticed that the other Haitians present seemed very hesitant to look this gentleman in the eye. I was later told that he was the most feared man in the country. Shortly thereafter, the hearse containing the young student's body arrived and we loaded it on the aircraft. As we loaded, I noticed that no one save for the soldiers and the Macoute was visible in this area of the airport.

We taxied to the end of the runway and, as I added power for take off, I could see a lighting filled sky awaiting the big Douglas. Our route to Miami took us a little to the east of the island of Cuba, and that appeared to be the area of the most severe weather. Approaching Cuba we ran into severe turbulence and were forced to a lower altitude and a course that took us closer to Cuba than I would have liked. I had visions of Migs checking my six. My co-pilot was having increasing difficulty maintaining radio contact with Miami, and was becoming concerned with our proximity to Cuba. The weather was getting even worse and forcing us to descend further and move closer to Fidel's Cuba. I knew from my own experience in Navy day fighters that it was extremely unlikely that any Migs were lurking about in these thunderstorms. I told my co-pilot to quit worrying about the Fidelistas and use the radar to find us a way out of this weather. After about forty minutes, the skies cleared and communications were restored. The rest of the trip was uneventful, and we landed in Miami and off loaded at customs.

I never heard or saw any mention of the incident in local news, and to this day I have been unable to find it in the records of the area newspapers. I did hear later that the girl had been killed by a common thief. After that incident, things gradually got worse in Haiti, and we eventually ceased service to the country. Baby Doc was overthrown in 1986.

This article originally appeared in the 1st Quarter 2005 print issue of LOGBOOK magazine.

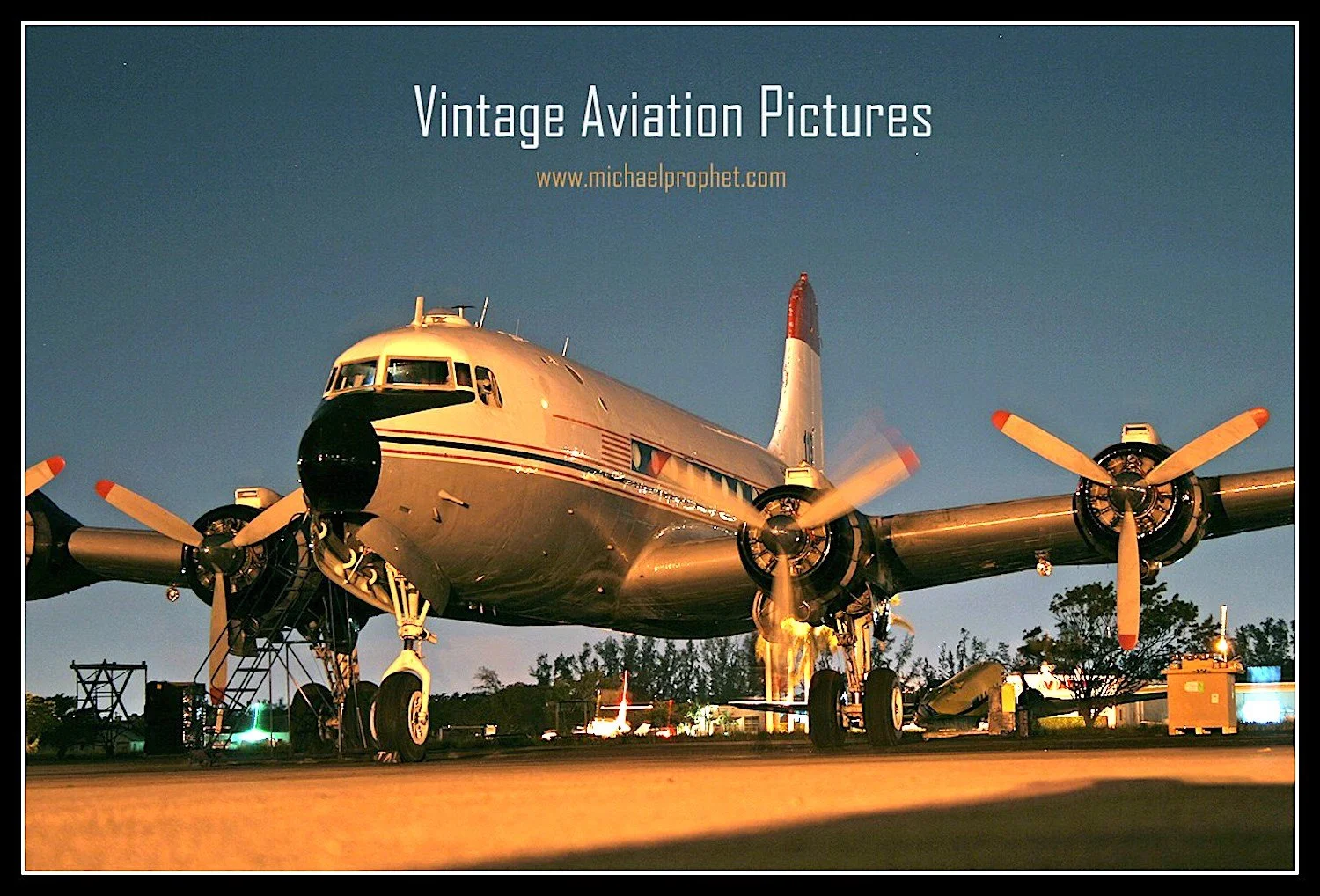

Somewhere out in the Bahamas, a Trans Air Link Douglas DC-6 awaits its next cargo run. The Company’s radio call sign was “Sky Truck.”

Photo: A.A.S. Collection

File photo of one of Trans Air Link’s Douglas DC-6A freighters - N874TA. This bird was originally delivered to the United States Air Force as a C-118A - Serial Number 53-3270 - in June 1955. Ten years later, in July 1965, it was converted into a VC-118A. In February 1975, it was stuck off charge from the Air Force, and began a life with a number of civilian operators, being converted into a freighter in 1978. Trans Air Link bought the aircraft in the late 1970s, and flew it into the late 1990s. It was reportedly sold for scrap in 2003. Photo: A.A.S. Collection

What’s in a Name?

by

The LOGBOOK Staff

At first glance, it would appear that the name of a Naval Air Station (NAS) – or a Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS), for that matter – is also the name of the airfield located

on that station. For example, let’s say two Naval Aviators are chatting about an upcoming weekend cross-country flight. One of the aviators inquires of the other, “Where do

you plan to stop for fuel?” Wherein the other replies, “I think I’ll make a quick stop at NAS Pensacola for gas.”

While the above reply is technically correct, a more accurate – and historically more interesting – reply would have been, “I think I’ll make a quick stop at Forrest Sherman

Field for gas.”

It is an often-overlooked tidbit of aviation history that most of the actual airfields located aboard an NAS carry of different name than the parent NAS itself. And,

most of these airfield names are steeped in aviation history.

In the above example, one of the air facilities situated aboard NAS Pensacola, Florida is named Forrest Sherman Field. On 2 November 1951, the old Fort Barrancas

Airfield was renamed in the honor of former Chief of Naval Operation Admiral Forrest P. Sherman. Another facility aboard NAS Pensacola was the Station Field,

a name that was changed to Chevalier Field on 30 December 1936. This change was to honor Lieutenant Commander Godfrey de Chevalier – Naval Aviator Number 7. Today

Sherman Field is still quite active, being the home of training squadrons, as well as being home plate for the Blue Angels. Chevalier Field has long been decommissioned, the

site now being used as a basic and advanced enlisted training facility.

With all that said, it should be noted that while most Naval Air Stations were named for the location – NAS Pensacola, for example – some were named for

historical figures and not necessarily for their location. NAS Cecil Field, Florida, comes to mind. It was named in honor of Commander Henry B. Cecil – Naval Aviator

Number 42 – who perished aboard the dirigible Akron (ZRS-4) when it crashed on 4 April 1933. It should be noted that NAS Cecil Field got its start as a Naval Auxiliary

Air Station (NAAS), associated with NAS Jacksonville. Many NAASs were later upgraded to full NAS status, however they kept their original names. Another quick example

of this policy is NAS Whiting Field, Florida, which was originally an auxiliary field associated with NAS Pensacola. NAS Whiting is named in honor of Captain Kenneth

Whiting – Naval Aviator Number 16.

So, knowing that most airfields carried a different name than their parent NAS, here is a little quiz. Listed below are a few airfield names – can you match them with the parent NAS or MCAS? Some are simple, while others are rather more obscure.

Admiral A. W. Radford Field

Cunningham Field

Chambers Field

John Rogers Field

Hensley Field

Munn Field

Bordelon Field

The Answers:

Admiral A. W. Radford Field – NAS Cubi Point, Philippines. Dedicated on 21 December 1972, this field honored Admiral Arthur W. Radford, a former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Today, this field is closed.

Cunningham Field – MCAS Cherry Point, North Carolina. This airfield was dedicated on 4 September 1941, in honor of Lieutenant Colonel Alfred A. Cunningham, who was designated Naval Aviator Number 5, and Marine Corps Aviator Number 1.

Chambers Field – NAS Norfolk, Virginia. One of the only airfields not dedicated to an aviator or aircrewman, Chambers Field was named on 1 June 1938, in honor of Captain Washington I. Chambers, and early and enthusiastic advocate of Naval Aviation.

John Rogers Field – NAS Barbers Point, Hawaii. Named in honor of Commander John Rogers, an early pioneer Naval Aviator. Dedicated on 10 September 1974.

Hensley Field – NAS Dallas, Texas. Interestingly, this airfield is not named for either a Naval nor Marine Corps Aviator, but rather for an early pioneering U.S. Army Aviator – Colonel William N. Hensley. In August 1930, the airfield, which was then an Army flying field, was named in his honor. The airfield retained this name, even after it became primarily a Navy facility. It is no longer an active military field.

Munn Field – MCAS Camp Pendelton, California. Munn Field was designated on 12 January 1987, in honor of Lieutenant General John C. Munn, a former Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps, and the first Marine Corps Aviator to command Camp Pendelton.

One thing common among all the above listed fields is the fact that they are all named after officers. This raises the question – Were any fields named for enlisted men?

Bordelon Field – associated with NAS Hilo, Hawaii. This field may not exactly meet the criteria listed above, but it is certainly worth mention here. Prior to the outbreak of World War Two there was a small civilian airport at Hilo, on the island of Hawaii. With the start of the war in the Pacific, the airport was taken over by the government, first by the U. S. Army Air Corps, and then in 1943, with an every expanding Navy presence. Eventually, the Navy portion of the field was commissioned a full NAS. On 19 April 1943, the airfield was named General Lyman Field in honor of U. S. Army Brigadier General Albert Lyman, a native Hawaiian and West Point graduate. Meanwhile, the Marine Corps carved out a small airstrip approximately 30 miles northwest of NAS Hilo, near the town of Kamuela, to be used as a liaison strip for the training that was being conducted in the area. This small 3,000-foot strip, which was under the control of NAS Hilo, was called Bordelon Field. It was dedicated in honor of Sergeant William J. Bordelon, an enlisted Marine who was killed on 20 November 1943, during the battle on the island of Tarawa. For his gallantry under fire, and his unwavering support of his fellow Marines, Sergeant Bordelon was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. Semper Fi. After the war Bordelon Field was soon closed, although there are vestiges of the field that can still be seen today. The Marine Corps continues to honor this fallen hero, as several facilities, structures, streets, etc… are named for Sergeant Bordelon.

How did you do? In another issue of LOGBOOK, we will bring you more interesting and sometimes little known names of airfields around the world.

This article originally appeared in the 4th Quarter 2009 print issue of LOGBOOK magazine.

The airfield aboard NAS Lakehurst, New Jersey - seen here during World War Two - was named on 6 January 1944, in honor of Commander Louis H Maxfield, who had perished back in 1921, in the crash of the dirigible R-38. Photo: U.S. Navy

Intelligence Narrative No. 51

Day Operations - 17 July 1943, 320th Bombardment Group

Mission: Bomb Central Railroad Yards, Naples, Italy

Aircraft: Martin B-26 Marauder

They’re Old and Slow, But These Two Old Veterans Are Dearly Loved By The Pilots At The Yuma Proving Ground

By

Phillip T. Washburn

Photos: Kimberly Connaway

R.T. Foster’s artwork is now curated by his daughter Heather Foster. She can be reached at:

R.T. Foster Art

405.632.8658 or rtfosterart@gmail.com

R.T. Foster - seen here in 2003 - airbrushes an illustration of an F-16 Fighting Falcon. Three paintings by the longtime illustrator are on permanent display at the Oklahoma state capital, and his work also hangs in galleries from the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum to the San Diego Air and Space Museum. Photo: U.S. Air Force

Hidden (now gone) Artifact in San Juan

by

Dave Powers

During a recent (2014) layover in San Juan, Puerto Rico, I decided I needed to walk off a particularly large

dinner, so I left my hotel on the Laguna del Condado and headed east on Avenida Ashford. About a mile

or so up the road, which is dominated by high-rise hotels and new condominium buildings, I saw tucked

away in a corner and somewhat obscured by a fence, what appeared to be the tail of an airplane. Not a real

tail, but rather an impressionistic image of an airliner's empennage on the wall of a building. I crossed the

avenida for a closer look.

What I found was a crumbling advertisement, actually a mosaic tile billboard of sorts, for the old Trans

Caribbean Airways, which noted the fact that the airline serviced New York, San Juan and Aruba. The billboard,

nearly 12 feet tall, was part of an exterior wall of a small shop or office building. Perhaps in the old days this

was Trans Caribbean's ticket office, as some unconfirmed references state. Today, many of the tiles are

missing, and with the amount of construction going on in the vicinity, the future of this rather unique old

artifact of airline history is certainly in question.

Trans Caribbean Air Cargo Lines was formed in May 1945, by O. Roy and Claire Chalk, with its main offices

in New York City, and its operational hub based at San Juan. In 1948, the name was changed to Trans

Caribbean Airways. Over the years the airline operated a variety of airliners, including Curtiss C-46s, Douglas

DC-3s, DC-4s and DC-6s, while later equipment including the Boeing 727, a number of versions of the

Douglas DC-8, and occasionally a Boeing 707 under lease. In addition to the above noted destinations, Trans

Caribbean also variously flew into Newark, New Jersey, Washington DC, Curacao, Haiti, and most of the U.S.

Virgin Islands. Passenger, mail and air cargo flights were flown, and both scheduled and chartered operations,

the latter often for the U.S. Military Airlift Command (MAC), were offered. In 1971, Trans Caribbean Airways

was absorbed in to American Airlines.

I don't really know if there is any interest in trying to preserve this piece of airline history, but it would be a pity to see it go, all the same. Like I said, there is a lot of demolition and construction going on this area, so its future is probably in some doubt.

Update: In April 2024, I did a walk - a digital walk via an online map service - up the Avenida Ashford looking for that mural. Alas, I found the building in question but the mural was gone. Perhaps it was just covered up, to be re-discovered another day. If it was removed I am not certain where it went. Most likely it is just gone. Pity

And speaking of DC-4s in San Juan ... please see the short article in the sidebar below.

The original version of this article appeared in the Volume 12, Number 3 - 3rd Quarter 2014 - print issue of LOGOOK magazine.

A wonderful period photo of a Trans Caribbean Airways Douglas DC-8, on the ramp at John F. Kennedy International Airport in 1970. A DC-8-54CF - (MSN 45684) - it was delivered new to Trans Caribbean on 16 December 1963. It was titled: Peter Jonathan II. The DC-8-54CF - the “CF” meaning Combi-Freighter, or alternatively Convertible Freighter was marketed by Douglas as a DC-8-54JT - the “JT” meaning Jet Trader. In any case, the airframe could be configured as pure passenger, pure cargo, or a combination of both. When Trans Caribbean was absorbed by American Airlines in March 1971, this DC-8 was placed in storage. Sold off in 1975, it flew for several years as a pure freighter before being scrapped in 2001. Photo: With the kind courtesy of Steve Williams

And Speaking of DC-4s in San Juan...

I have been flying in and out of Luis Muñoz Marin International Airport, at San Juan, Puerto Rico, for nearly

thirty years now (well at least through 2014). Although I was never based there, I always enjoyed passing

though San Juan's airport, either on a quick turnaround or for a few days of welcome layover. One of the

things I particularly liked about this airport was seeing a vast array of round-motored airliners still hard at

work. There were birds from such manufacturers as Douglas, Convair, Lockheed, Curtiss, Beechcraft and

others, all powered by various round piston engines. These birds were no pampered hangar queens trotted

out on a sunny day, but rather viable commercial aircraft that had to fly to make a living. The ramps were

oily and the air was full of blue exhaust smoke. Neat!

Well, over the years the number of these machines working out of San Juan has decreased dramatically.

Today, I am still flying into San Juan, but, while there are still a few left, it is harder to find any round-motored

aircraft.

A couple of months ago, we were pulling into the south cargo ramp, a ramp that used to be full of DC-3s

waiting to take our cargo out the smaller islands, when I saw a image from the past. Sitting on the eastern

edge of the cargo ramp was a Douglas DC-4 freighter, looking quite nice in the noontime tropic sun. After

we shut down, I asked our local mechanic about the DC-4. He said it was recently a frequent visitor to the

airport, tramping general cargo around the islands.

So here's the story: This bird is a Douglas C-54G-1-DO Skymaster, which was delivered to the United States

Army Air Forces on 19 June 1945, with the Serial Number 45-0491 (MSN 35944). After a long career, it was

retired from active duty in January 1972, and placed in storage at Davis Monthan Air Force Base. Over the next

few years the airframe changed hands several time, first being bought by Dross Metals on 13 November 1975,

who sold it to WAIG Aircraft on 10 November 1976. On 30 March 1979, WAIG Aircraft first placed this C-54G

on the civilian register as N406WA. In 1981, WAIG Aircraft was dissolved, with several of the company officers

forming ARDCO, Inc., based in Tucson, Arizona. On 15 January 1982, ARDCO purchased the aircraft, and

converted it for aerial firefighting with the addition of a large ventral suppressant tank. It was called Tanker 119.

After the turn of the century, U.S. Forest Service officials began to question the future of these large

recip-powered tankers. With the future of aerial firefighting clearly going to newer turbine-powered aircraft,

N406WA was pulled off the line, and ultimately sold to Florida Air Transport in December 2007. The

suppressant tank was removed and a cargo floor installed. Based at Opa Locke, Florida, N406WA began

flying cargo from Florida out the islands. Then, on 28 October 2011, the aircraft was again sold, this time to

Jet One Express, of Davie, Florida, where it continued general cargo runs throughout the Caribbean.

As the mechanic and I walked over to N406WA, to take a few photos, he asked me if I had heard what had

happened to the bird. I confessed that it looked as if the old C-54 was rather inactive, but I had not heard any

news. Well, on 22 March 2012, while taxing in from a normal run, the nose landing gear collapsed and the aircraft settled down on to its nose. When I took these photos, repairs were currently underway, however as of this publication, N406WA has not yet returned to the air.

Anybody out there see N406WA back in the air? Please drop us a line - thanks.

The original version of this article appeared in the Volume 12, Number 3 - 3rd Quarter 2014 - print issue of LOGOOK magazine.

Update: Sometime after its untimely accident in 2012, inspections indicated that main wing spar corrosion was advanced to the point where repairs were beyond economical consideration, and the airframe was scheduled to be scrapped. In the meantime, when Hurricane Maria rolled through Puerto Rico in September 2017, the airframe was picked up and unceremoniously tossed into a nearby drainage ditch, further sealing its fate. In 2020, N406WA was scrapped at San Juan.

Above: Douglas C-54/DC-4 on the cargo ramp at San Juan, Puerto Rico, as I saw it on 12 June 2014. This was after the bird had suffered a nose gear collapse, and I was told that repairs were underway. History would show that it never flew again. This aircraft was familiarly known as a “Super 4.” Along with at least one other DC-4 in the ARDCO fleet, it as modified when the original Pratt & Whitney R-2000 twin wasp engines were replaced by a set of Wright R-2600 Twin Cyclone engines. Although there was a modicum of increased performance, the main advantage was the relatively large number of spare R-2600 engines then available. Photo: A.A.S.

Below: better days - a great photo of N406WA on the ramp at Opa Locka, Florida, firing up for a hop down to the islands. Photo by Michael Prophet, ace photographer, round propliner enthusiast, and LOGBOOK contributor. Thanks Michael

A Flying Dumpster?

The North American T-28B/C Trojan was powered by a Wright Cyclone R-1820 radial engine. The Grumman TF/C-1A Trader was powered by two Wright Cyclone R-1820 radial engines (as were the S2F/S-2 Tracker, the WF/E-1 Tracer, the TS-2 multi-engine trainer and the US-2 utility bird). Those old timers out there - like me - who flew the T-28B/C Trojan used to quip that the C-1A was nothing but two T-28s flying in really close formation.

Not long ago I received a note from Deke, an old Navy buddy of mine, a former T-28B/C pilot like myself, and now a senior captain at American Airlines. Deke wrote: “Hey Dave, as a fellow Hog Driver [referring to the Trojan] you will appreciate this. I was flying with a guy who was one of the last C-1 Trader Drivers in the Navy. When I mentioned that it had the same motors as our T-28s he replied, ‘Yup, the C-1 was basically two T-28s bolted to a dumpster.’”

Ha! Good one, Deke!

Fly Navy,

Dave Powers

The original version of this article appeared in the Volume 14, Number 3 - 3rd Quarter 2020 - print issue of LOGOOK magazine.

Above: A file photo of a Grumman C-1A Trader - BuNo 136769 - trapping aboard the USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63). Photo: National Naval Aviation Museum, click HERE to stop by.

Soviet Taran*

by

Dave Powers

You just never know when you are going to stumble upon a bit of aviation history. Sometimes just a simple mention of a person,

airplane or event can send you off on a quest for more information and you end up digging up facts on a flying story that you have

never heard of before. And, if there is a little “cloak and dagger” involved, well that’s ok, too.

A few months back I was at my doctor’s office on a routine visit. My doc was born in Argentina, but his family emigrated to the

U.S. when he was still a baby. After med school he served as a U.S. Air Force doctor, and as such has always had a more than

passing interest in flying. Knowing that I was well into all aspects of aviation, every visit we had was accompanied by rousing

conversations on flying - much to the consternation of his nurses, who were trying to keep is appointment book on schedule. It

was during this visit that he told me about a flying episode that I had never heard of before.

I really don’t know how our conversation turned to the topic, but soon we were talking about clandestine flights - all hush hush,

spooky, spy game stuff. He then mentioned that his father had a very close friend who was long ago shot down over the Soviet

Union during a cargo flight. Although unverified, my doc said that the cargo carried, and the flights themselves, were all somewhat

dubious, and had more than just a hint of covert ops about them. The incident took place nearly 40 years ago, and my doc could

not recall any more specific details. So I started digging, and this is what I found out.

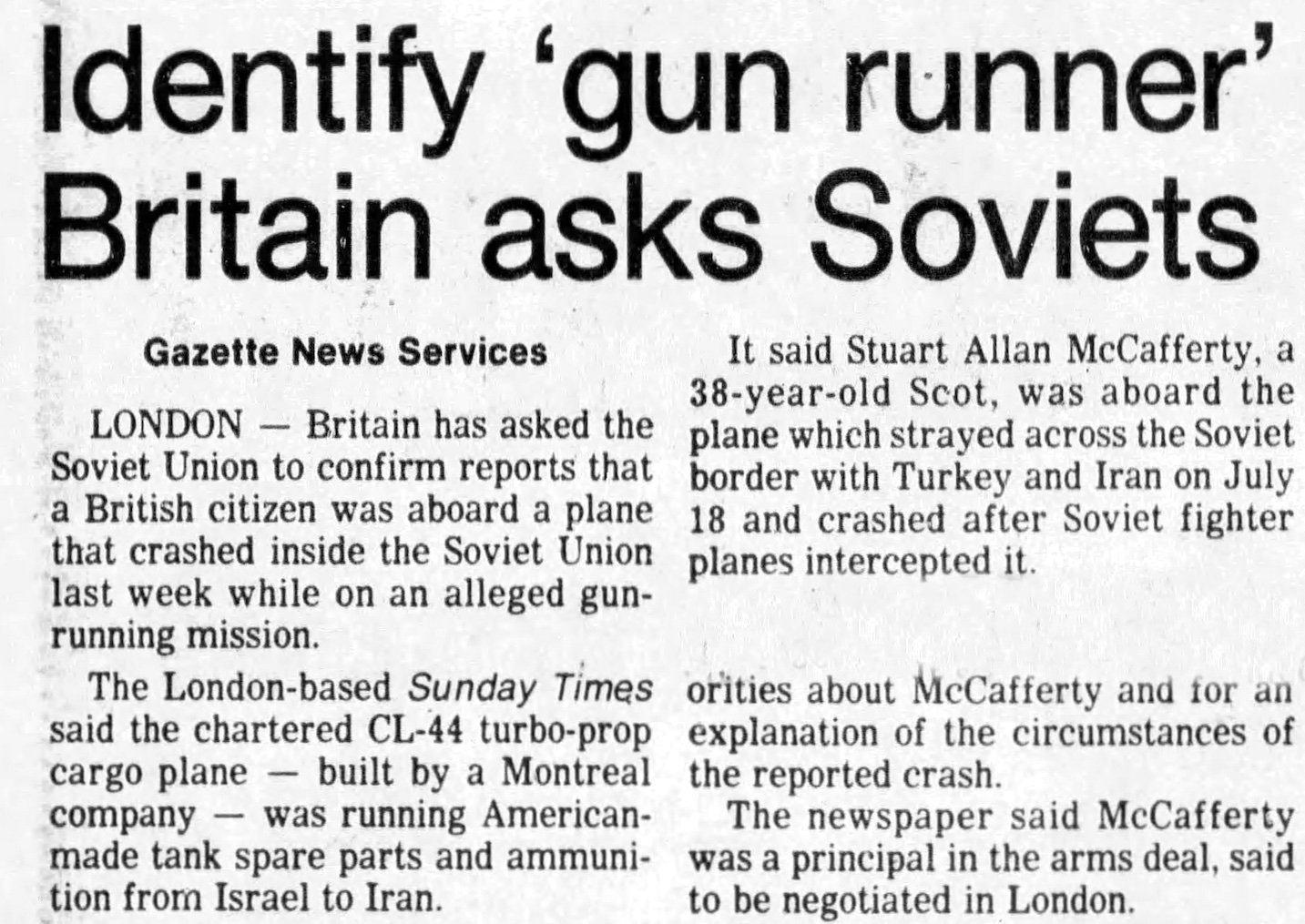

On 18 July 1981, a cargo airplane from a little known Argentine cargo airline crashed just inside the border of the Soviet Union.

The freighter did not simply crash, nor was it shot down. Instead it was brought down after it was rammed by a Soviet fighter.

The cargo bird in question was a Canadair CL-44D4-6, a big, four-engine turboprop freighter, one of 39 examples built. Registered

as LV-JTN - construction number 34 - this particular airframe was one of two of the type in the fleet of a charter cargo outfit called

Transporte Aereo Rioplatense (TAR). LV-JTN was first delivered to Slick Airways - as N605SA - back in October 1962. After a number of various operators, it was finally bought by TAR on 10 April 1971.

Despite all my digging, the back-story to this incident has remained elusive, so the following may be open for discussion. It appears that in the early 1980s, certain “intermediaries” for the Israeli government contracted TAR to fly a number of cargo flights from Tel Aviv, Israel to Tehran, Iran. It should be pointed out that this was a practical application of the concept of “always support your enemy’s enemy,” since during this time Israel, although not overtly, tended to support Iran because Iran was then fighting Israel’s even worse enemy, namely Iraq. The flights clandestinely loaded in Tel Aviv, but would then fly first to Larnaca, Cyprus, before flying on to Tehran. Officially, the flights were round trips between Larnaca and Tehran, hopefully eliminating any connection with Israel, and at least on this flight, the cargo manifest reportedly read “tires.” What was actually being carried is open to supposition.

Captain Hector Cordero was in command of the flight, assisted by co-pilot Hermete Boasso and engineer Jose Burgueno, the latter being the friend of my doctor’s father. Also on board was a mysterious Scotsman by the name of Stuart McCafferty, who was listed as a “purser,” but was thought to be a representative of whoever was sponsoring the flight. He was supposedly on board to keep an eye on his cargo. This was the third such flight for this crew, and the inbound leg and cargo drop was completed without incident.

Flying northbound out of Tehran, as he had done twice before, Captain Cordero guided his freighter along the border of Iran and what was then Soviet Azerbaijan, thus avoiding any unpleasantness stemming from flying too close to the Iran/Iraq conflict. Once in Turkish airspace it would be an easy turn to the west and back to Cyprus. What happened on this northbound leg is really anybody’s guess, as all details came rather one-sidedly from the Soviets. The TAR CL-44 crashed within sight of the Araks River - the border between Turkey and Azerbaijan - and just inside Soviet territory.

What caused the crew to allow the aircraft to stray off course is anybody’s guess, probably just a small navigational error. The result, however, was that Soviet air defense launched several fighters from the 166th Fighter Regiment, although only one actually managed to catch the wayward freighter - a Sukhoi Su-15TM Flagon, piloted by Soviet Air Force Captain Valentin Kulyapin. It is from his report, certainly heavily edited by Soviet officials, that we learn of the last moments of the TAR CL-44.

Captain Kulyapin, who one source notes was the squadron’s political officer - the zampolit - and was more of a Soviet ideologue rather than a good pilot, states that he used all the normal, internationally accepted, procedures to intercept and communicate with a civilian aircraft. He states that rather than following his signals the crew of the CL-44 either ignored his instructions or responded with aggressive maneuvers. The freighter then made a sharp turn to the west, in an apparent attempt to flee Soviet airspace. Since Kulyapin’s fighter was not equipped with an internal gun - the Su-15 could carry gun pods, but apparently Kulyapin’s aircraft was not so equipped - and there was no time to drop back for a missile shot, he decided, in the spirit of a true Soviet hero, to simply ram the intruder. Which he did, causing catastrophic damage to both this fighter and the CL-44. Kulyapin ejected, and survived, while all four aboard the CL-44 perished in the resultant crash.

After the incident there was a minor diplomatic confrontation between Argentina and the Soviet Union, which the latter managed to initially brush off by saying that the fighter pilot - Captain Kulyapin - had also perished. Since there were no eyewitnesses left to corroborate why the CL-44 went down, the Soviets said it was a simple accident, and that was the end of that. The CL-44 was flying empty, so there was no nefarious cargo to implicate the crew. The bodies of the crew of the CL-44 were returned to their respective countries and the whole episode was soon forgotten.

Of course, Soviet propagandists could not pass up the chance for a good patriotic story. Several years later Captain Kulyapin’s tale of his interception and downing of the TAR CL-44 was chronicled in a two page spread in the 6 April 1986 issue of the Soviet military journal Krasnaya Zviezda - the Red Star - which prominently displayed a photo of the hero fighter pilot. The article was peppered with lines like: “The intruder aircraft’s shadow fell on our territory - an evil nasty shadow.” Captain Kulyapin remembers asking himself, “Who would dare cross our border?” And, when the CL-44 turned to the west he concluded, “He won’t get away.”

Of course, there could be another version of the story. Some commentators in the West posited that the crew of the CL-44 never even saw the Soviet Flagon, and perhaps not knowing they were in Soviet airspace simply made the normal left turn to fly west over Turkey. Captain Kulyapin could have interpreted this turn as either an evasive or an aggressive maneuver. Perhaps, Captain Kulyapin, when trying to flying in close to the freighter got caught up in the propwash of the CL-44’s four big Rolls-Royce Tyne turboprop engines, and got tossed into the freighter. Maybe, due to poor airmanship, the Soviet fighter pilot just hit the CL-44 by mistake. In any of these scenarios, only Captain Kulyapin was left to tell the truth.

* Taran - A Russian word for "battering ram."

The original version of this article appeared in the Volume 14, Number 3 - 3rd Quarter 2020 - print issue of LOGOOK magazine.

Long range shot of Transporte Aereo Rioplatense’s (TAR) Canadair CL-44 - LV-TJN - seen on the ramp at Miami International Airport - October 1979. TAR was founded in December 1969, by Carlos F. Martinez Guerrero, and was headquartered in Buenos Aires, Argentina. By the start of the 1990s, TAR had ceased operations. Photo: Charlie Stewart via Air-Britain

A headline from the Montreal Gazette - 28 July 1981.

Photo: U.S. Air Force

Preservation

Lockheed SR-71A Blackbird “Big Tail”

Serial Number 61-7959

U.S. Air Force Armament Museum

Eglin Air Force Base, Florida

Few, indeed, are the aircraft - actual production aircraft, not one-off prototypes - that when the type is finally fully retired from

active service each and every airframe that was built is preserved in a museum. In the civilian world, probably the best example of

this would be the Anglo-French Concorde. When this airliner was ultimately withdrawn from service there was sort of a mad

scramble by museum curators to get one of the few airframes built donated to their institution. And, of course, all of NASA’s

extant Space Shuttles (STS or Space Transportation System) are preserved. In military aviation, when the Lockheed SR-71 was

retired, save those airframes that were lost in accidents, each airframe was donated to a museum and is now preserved. None were

put under the scrapper’s torch.

One Lockheed SR-71 that is on display is the A-Model airframe - Serial Number 61-7959 - that today can be seen at the U.S Air

Force’s Armament Museum, located aboard Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. Even a cursory examination of this bird would reveal

that this is not a “stock” SR-71A, as it has an unusual, extra long tail. It was this extended tail fairing that would give this SR-71A

the unofficial moniker of “Big Tail.”

The Blackbird has always been a highly capable aircraft, a super-fast, high flying reconnaissance platform that has never been

equaled by any other, even to this day. In 1974, long after the Blackbird had proved its worth, U.S. Air Force officials wanted a bit

more. Even though the airframe was already filled with either aircraft systems or reconnaissance gear, these officials looked for a

way to pack more into or onto the airframe. In addition to more spy-gear, the Air Force wanted to mount more sophisticated

Electronic Counter Measures (ECM) equipment to counter a perceived growing threat.

Several ideas were forthcoming, including various modifications to the airframe, basically bumps, fairings or protrusions

appended onto the fuselage, as well as removable belly pods. In the end it was decided to extend the fuselage aft of the

tail. At some 13 feet, 9 inches long, with a volume of 49 cubic feet, this extension, essentially just a large tail cone, certainly fit the

bill. Aerodynamically, it was also the most appropriate.

Blackbird “959” - the tenth airframe built - was selected to be the test bed, mainly because of the fact that since it was part of the stable of test and development birds, it would not require removing an operational aircraft from a front line reconnaissance squadron. Due to the fact that the extension would drag on the ground as the aircraft rotated for take off, and during landing, the whole assembly was articulated and could be repositioned up some 8.5 degrees. During the landing phase, once the aircraft was one the ground and level, the extension would quickly be repositioned back down so the aircraft’s drag chute could be deployed. First fight with the “Big Tail” installed was logged on 3 December 1975, and was kept subsonic. On 11 December the first sonic flight was logged, with no apparent degradation in performance or handling. On 28 January 1976, “959” was flown at Mach 3+, at 75,000, and everything looked good.

Some 36 Lockheed/Air Force test flights were made with the new tail, carrying various ECM gear and camera set ups, and although everything worked as envisioned, the Air Force terminated the project. On 29 October 1976, “959” logged its last hop, have recorded 866 hours during 304 missions. The airframe was then placed in storage and used as a source of spares for the rest of the SR-71 fleet. Finally, in 1991, it was put on display at the USAF Armament Museum.

The address of the USAF Armament Museum is technically on Eglin Air Force Base, however the museum is actually located in an area that is open to public access. So, although increased base security measures will be in force for the foreseeable future, limiting access to non-military folks to the actual base, getting to the museum is easy, with no additional security protocols. The museum is located less than one hour south of Interstate 10, that runs east/west through the Florida panhandle, so it’s an easy detour on your travels through the state.

The original version of this article appeared in the Volume 14, Number 3 - 3rd Quarter 2020 - print issue of LOGOOK magazine.

Top: Lockheed SR-71A Blackbird “Big Tail” - Serial Number 61-7959 - on display at the USAF Armament Museum at Eglin Air Force Base.

Above: A close up of the articulated tail cone extension. The idea was to fill this extra space with various cameras and/or defensive electronic gear. Both Photos: A.A.S.

Blackbird “959” being refueled by a Boeing KC-135Q Stratotanker - Serial Number 58-95. The “Q” model KC-135 was a modified KC-135A with special fuel tanks to carry the unique JP-7 jet fuel required by the SR-71’s Pratt & Whitney J58 engines. Photo: U.S. Air Force

Preservation

Republic F-84F Thunderstreak, Serial Number 51-9422

American Legion Post 253

Festus, Missouri

Mounted on pylons just outside the American Legion Post, this Republic F-84F Thunderstreak is dedicated in the name of Major Julius V. Santschi (1923-2005), a local Festus, Missouri veteran. As a young man, Santschi joined the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War Two, flying missions in both Europe and in the Pacific, and receiving four Air Medals and two Presidential Unit Citations. After the War, he worked as a mechanical engineer, while also completing a career in the Missouri Air National Guard.

These photos were taken in 2015.

This article originally appeared in the 2nd Quarter digital edition of LOGBOOK magazine.

There are no 611s in HS-7

by

Dave Powers

My old Navy fleet squadron was the World Famous Helicopter AntiSubmarine Squadron Seven (HS-7), official name the

”Shamrocks”, call sign the “Dusty Dogs.” We flew the mighty Sikorsky SH-3H Sea King. At the time all aircraft on an aircraft

carrier were assigned side numbers (modex numbers) denoting their squadron and mission. These numbers were the same

throughout the fleet, regardless of individual squadron or ship. HS squadrons were all given side numbers starting with the

numerals 61. Since an average HS squadron had six aircraft, that would mean the numbering sequence would start with 610

and go through 615.

Now talk about superstitious. When I first checked into HS-7 back in the early 1980s they had just had an accident. The aircraft

was lost but the crew was Okay. The aircraft had the side number 611. About two years into my tour, in May 1986, we had another

accident, a ditching off the coast of Puerto Rico. Again, the aircraft was lost but the crew was fine. And again, the aircraft’s side

number was 611. When we got a replacement aircraft it was numbered 616. The side number 611 was just too unlucky.

You may think that the U.S.Navy is above superstition, but have you ever wondered why there is no HS-13?

Continue reading below.

The Sub Choppers of HS-13

For as long as HS squadrons have been in existence, the US Navy has based the even numbered squadrons on the West Coast

and the odd numbered squadrons on the East Coast. Thus HS-1, HS-3, HS-5, HS-7, HS-9, HS-11, HS-15 and HS-17 have always been East Coast squadrons. Many believe that there never was an

HS-13, which had something to do with the unlucky connotations of the number 13. Despite the harbingers of doom associated with the number, there was an HS-13 in existence in the early

1960s, if only for a few days over one year.

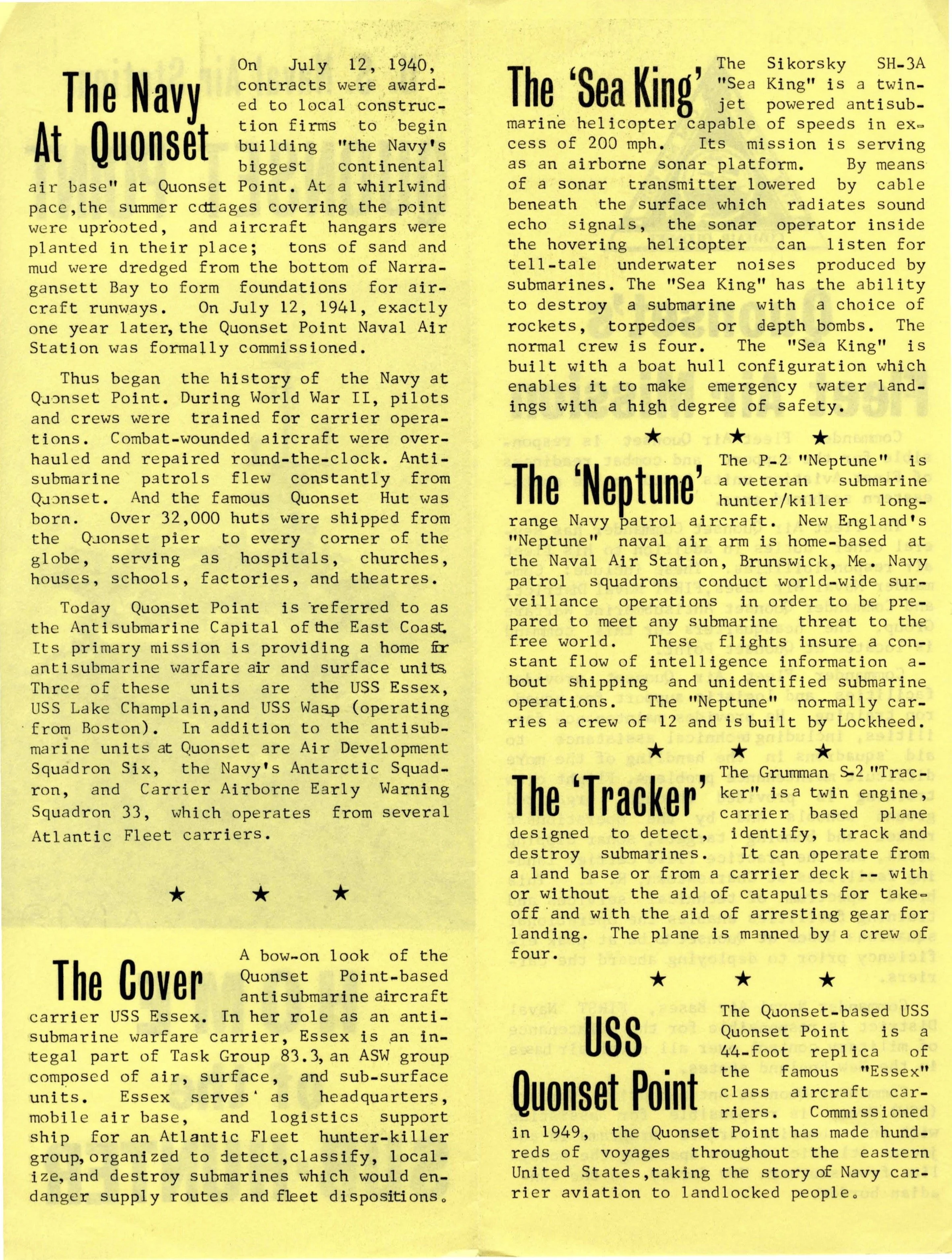

Helicopter AntiSubmarine Squadron THIRTEEN (HS-13) was established on 25 September 1961, as part of Anti-Submarine Carrier Air Group SIXTY-TWO (CVSG-62), which itself was stood

up on the same day. Shore based at Naval Air Station (NAS) Quonset Point, R.I., HS-13 was authorized a strength of up to 16 Sikorsky HSS-1N Seabats. The N model Seabat was optimized for

night and all weather operations. Also assigned to CVSG-62 was fixed-wing Anti-Submarine Squadrons TWENTY (VS-20) and FORTY-TWO (VS-42), both flying the Grumman S2F-1 Tracker.

Although HS-13 was authorized up to 16 HSS-1Ns, the squadron rarely had that many on strength. In September 1961, only 2 airframes were listed on hand, with four more arriving the next

month. At the close of 1961, HS-13 had 11 Seabats. Finally, in June 1962, the squadron had a full compliment of 16 Seabats. The exact date of the announcement that CVSG-62, and all its

squadrons, would be disestablished is not certain. However, the end was certainly clear because in July 1962, HS-13 had only one airframe still on the books. Indeed, VS-42 was completely

gone. By August 1962, the final HSS-1N was gone and HS-13 ceased to be listed as a viable squadron in September 1962. CVSG-62, along with HS-13, was officially disestablished on 1 October 1962.

There is one reference that questions whether or not HS-13 even existed, positing that the squadron was simply formed on paper. However, the January 1962 issue of the Navy’s Naval

Aeronautical Organization (OPNAV 05400) states that HS-13 was on board NAS Quonset Point, and had 49 officers and 262 enlisted personnel. Throughout its short existence, HS-13, nor

CVSG-62 for that matter, never deployed to sea.

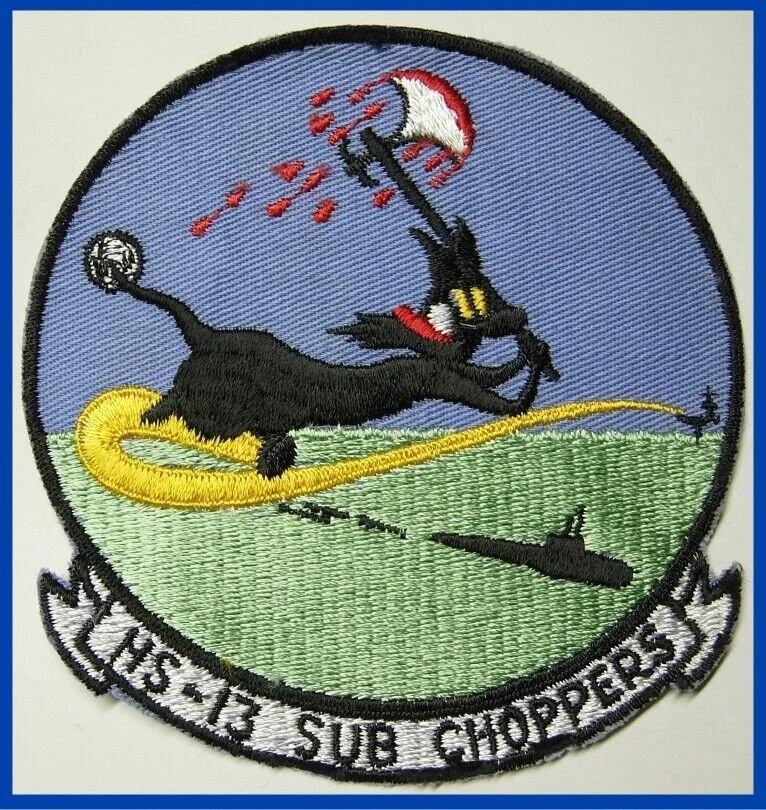

HS-13 was nicknamed the Sub Choppers. The squadron patch showed a cartoon cat, equipped with a tail rotor and flying off an aircraft carrier. The cat is carrying a bloody axe and is poised to

take a swing at a submarine.

Some squadrons are disestablished on one day, only to be reestablished later in the future. This never happened to HS-13. Perhaps the number 13 was indeed, unlucky.

This Sikorsky SH-3H Sea King - BuNo 149900 - today rests in a couple of thousand feet of water off the coast of Puerto Rico. Photo: A.A.S.

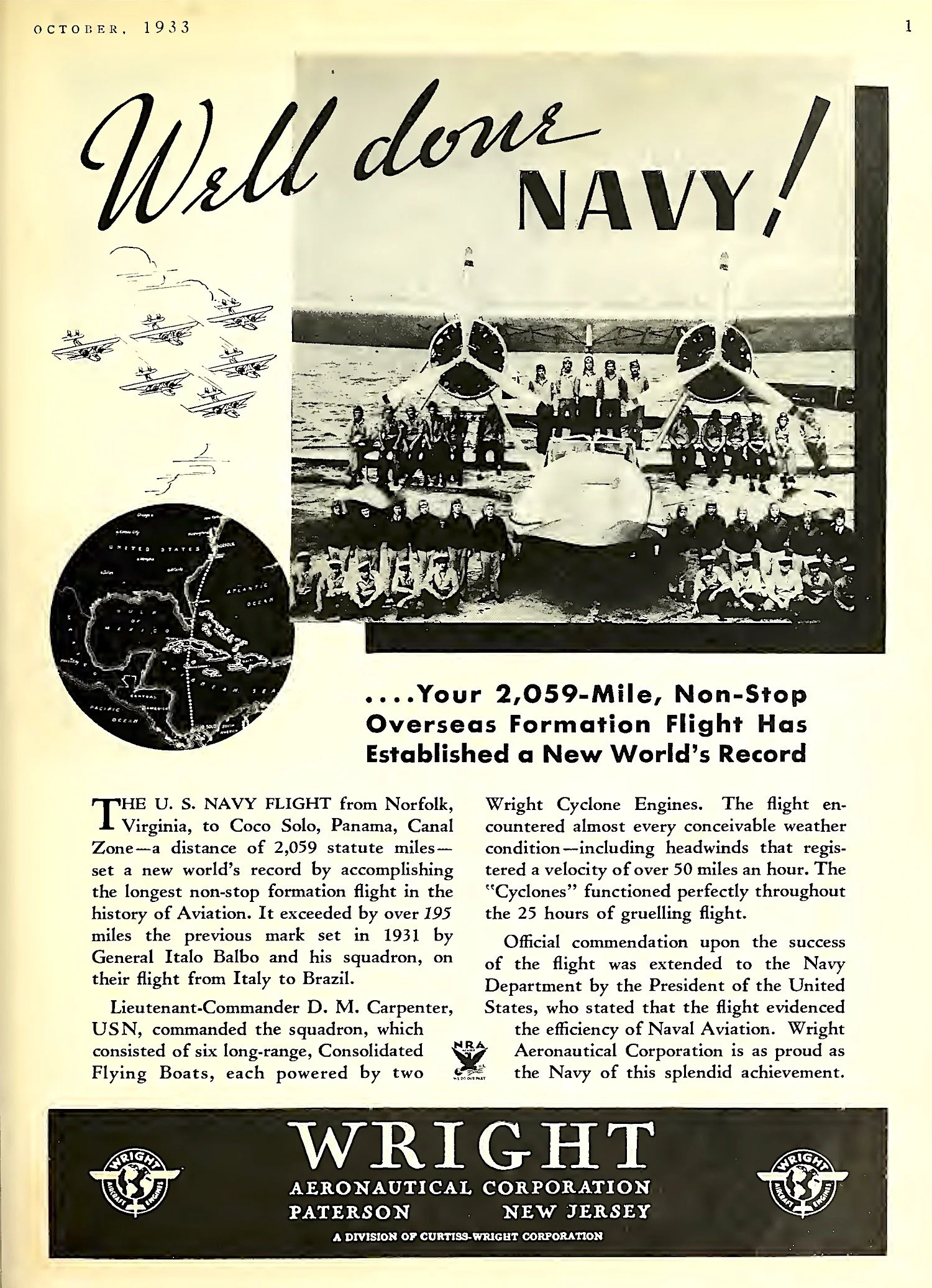

Coco Solo Ferry Flight

In the late afternoon of 7 September 1933, six Consolidated P2Y-1 flying boats, assigned the Patrol Squadron FIVE FOX (VP-5F), and under the command of Lieutenant Commander D. M. Carpenter, departed from Naval Air Station Norfolk, Virginia. Their destination - some 2,059 statute miles away - was the Fleet Air Base at Coco Solo, Panama Canal Zone. When they landed they had bested the then current formation distance record, set in January 1931, by the Italian Flight Squadron led by General Italo Balbo, by 195 miles.

References: Aviation magazine - October 1933, and Aero Digest - October 1933.

Right: A file photo of a Consolidated P2Y-1 flying boat, this example assigned to Patrol Squadron TEN (VP-10). Photo: NHHC

Left: An advertisement that appeared in Aero Digest magazine, from the Wright Aeronautical Corp., celebrating the flight. Image: A.A.S.

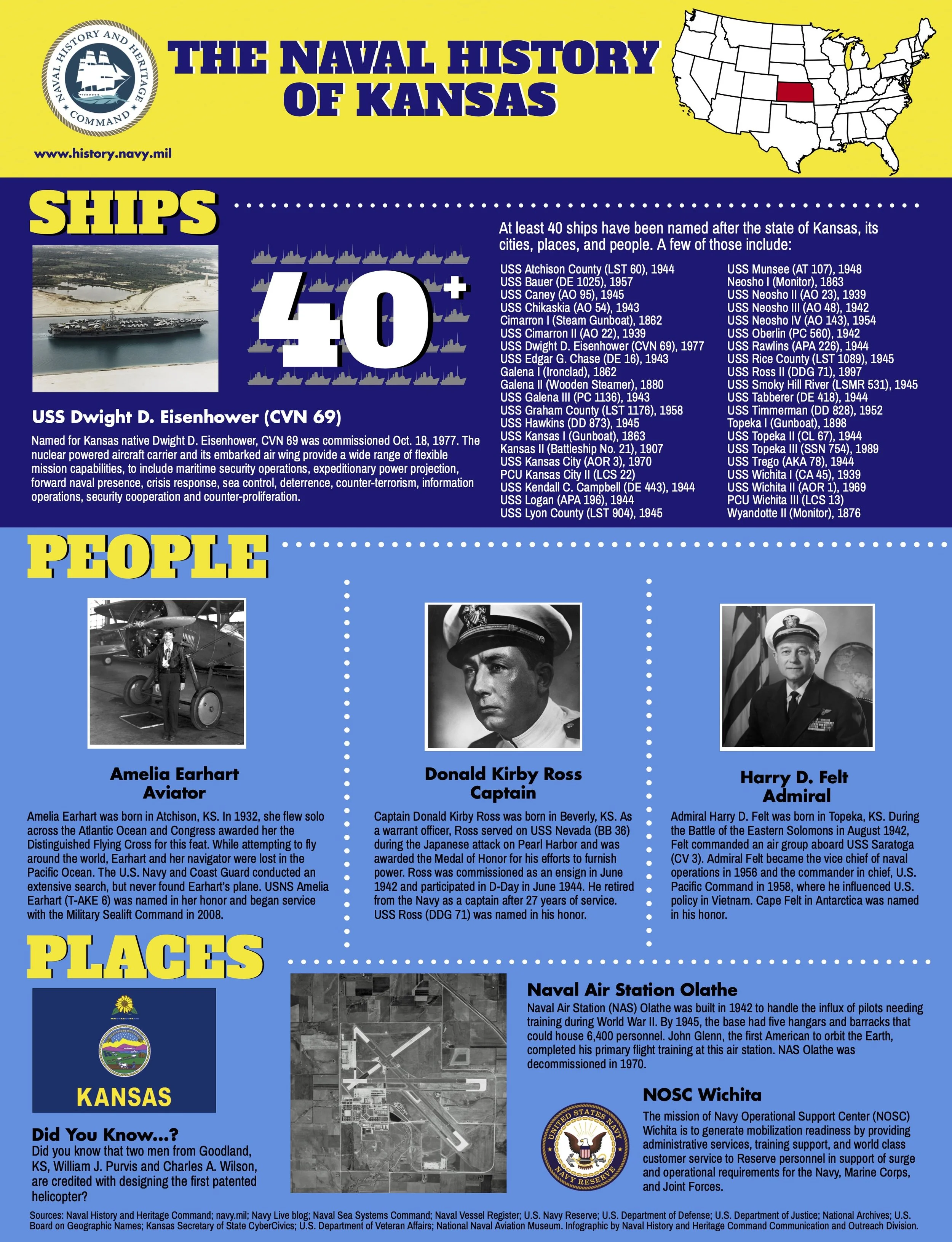

Graphic Courtesy of the Naval History and Heritage Command

Stop by at:

Naval History and Heritage Command

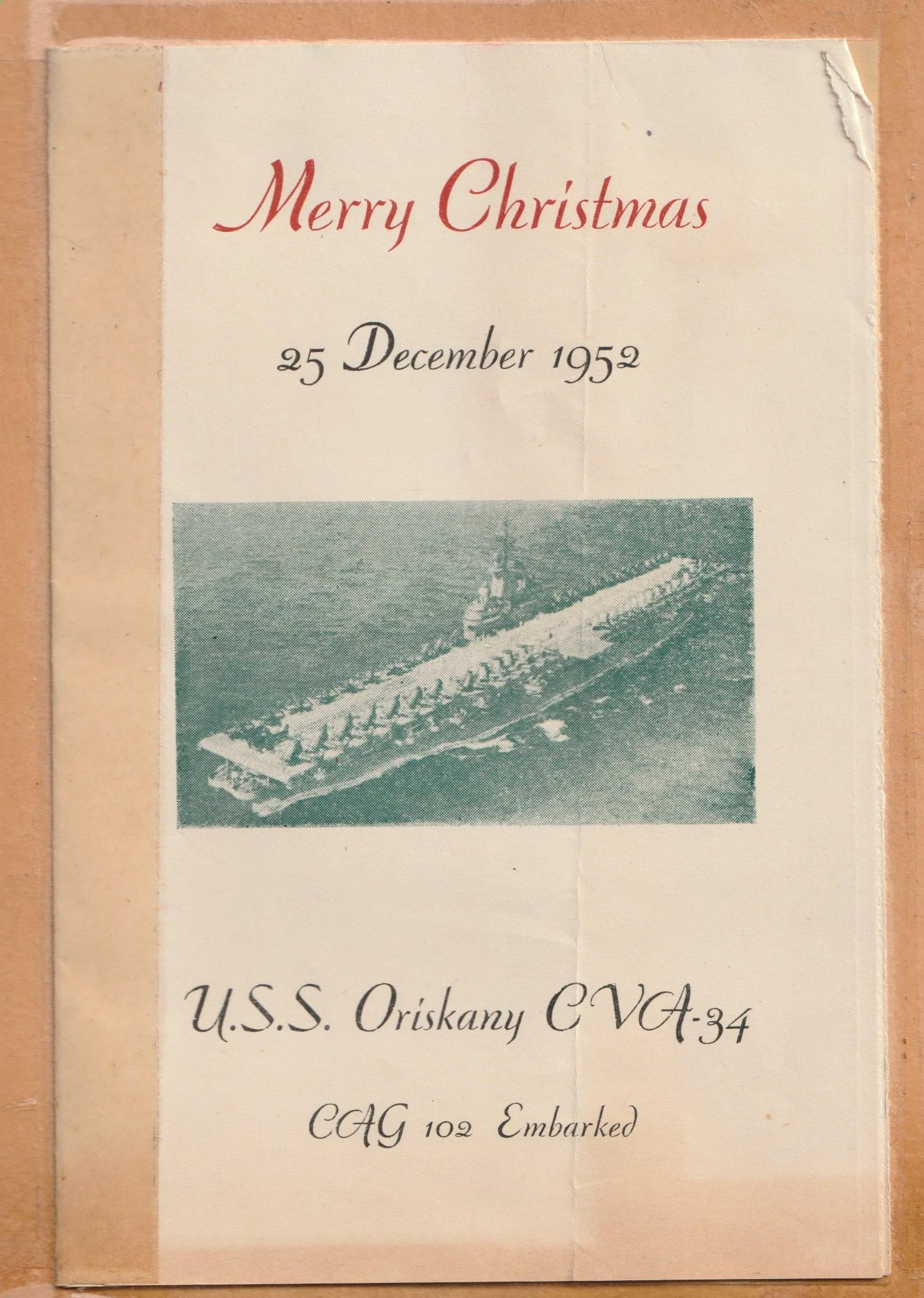

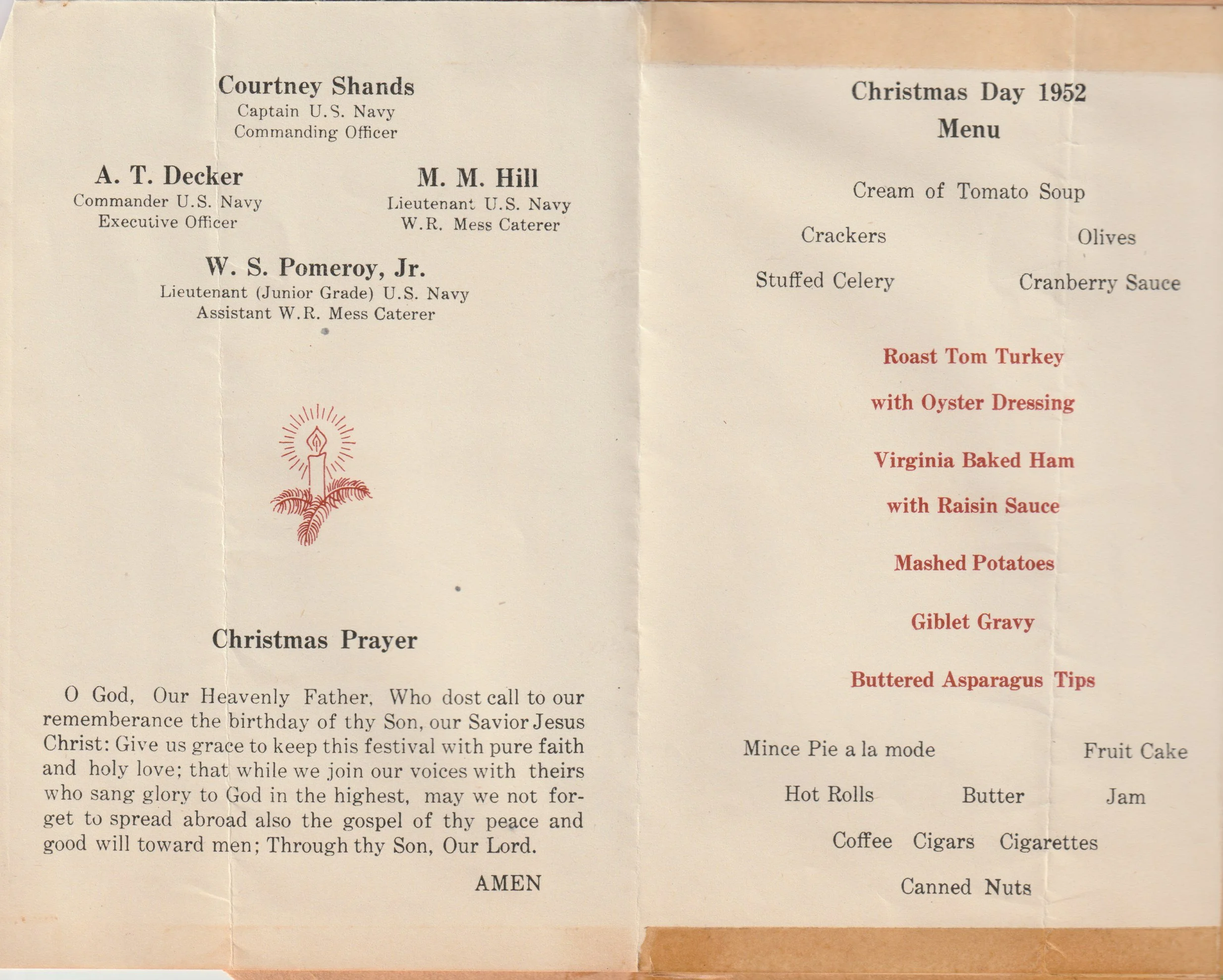

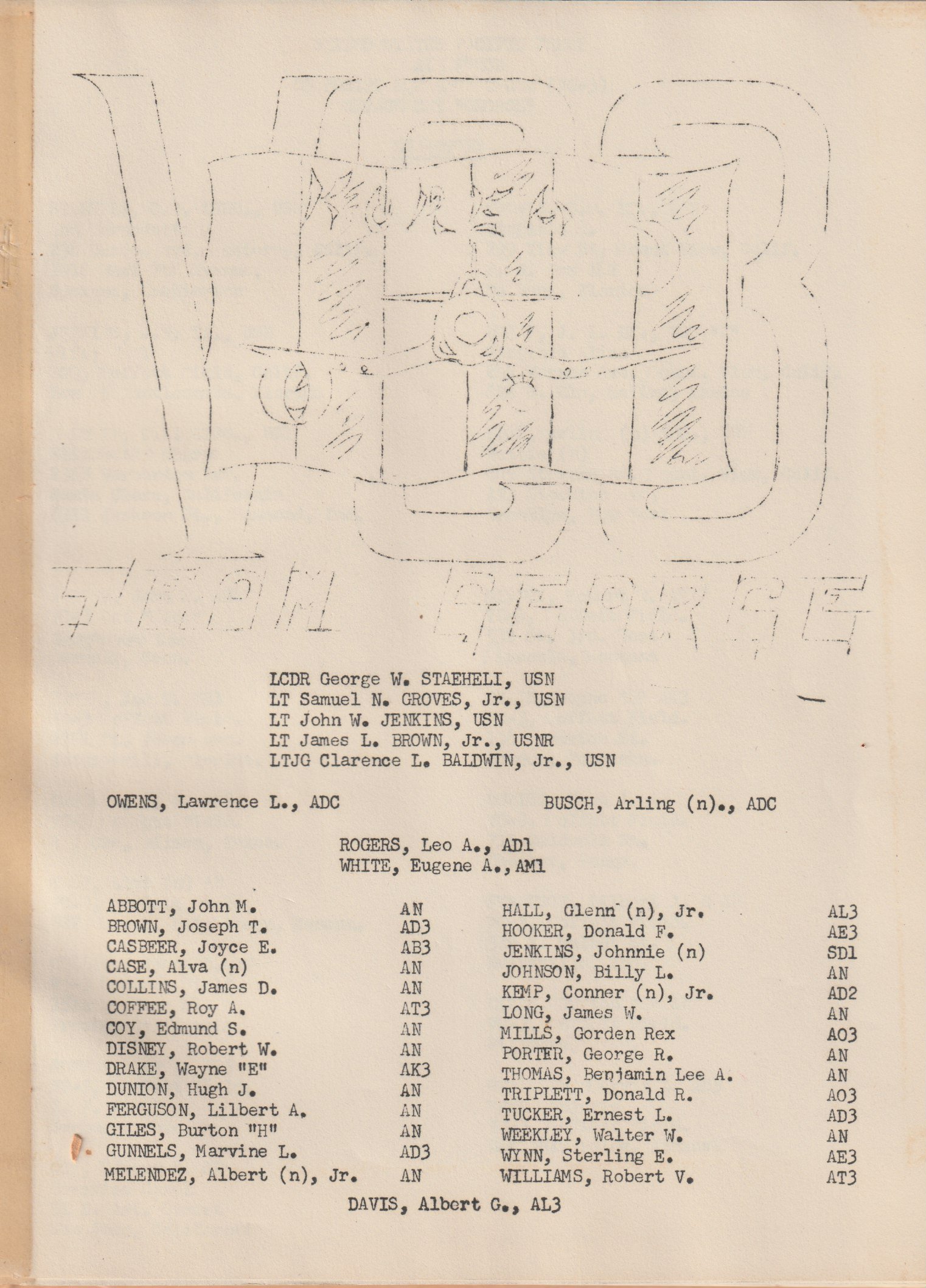

On 25 December 1952, the USS Oriskany, with Carrier Air Group 102 embarked, had just completed its second - of five - Korean War line periods, and was en route to Yokosuka, Japan.

From the Commander James L Brown, Jr. Collection (Jim was aboard with VC-3, Det. George, flying the F4U-5N Corsair night fighter)

From an informal history of VC-3, Team George’s Korean War cruise aboard the USS Oriskany (November 1953 to May 1953) - A poem about the trials of the Landing Signal Officer (LSO) bringing aboard the Team’s the Vought F4U-5N Corsairs.

From the Commander James L Brown, Jr. Collection (Jim was aboard with VC-3, Team George, flying the F4U-5N Corsair night fighter as a night heckler)

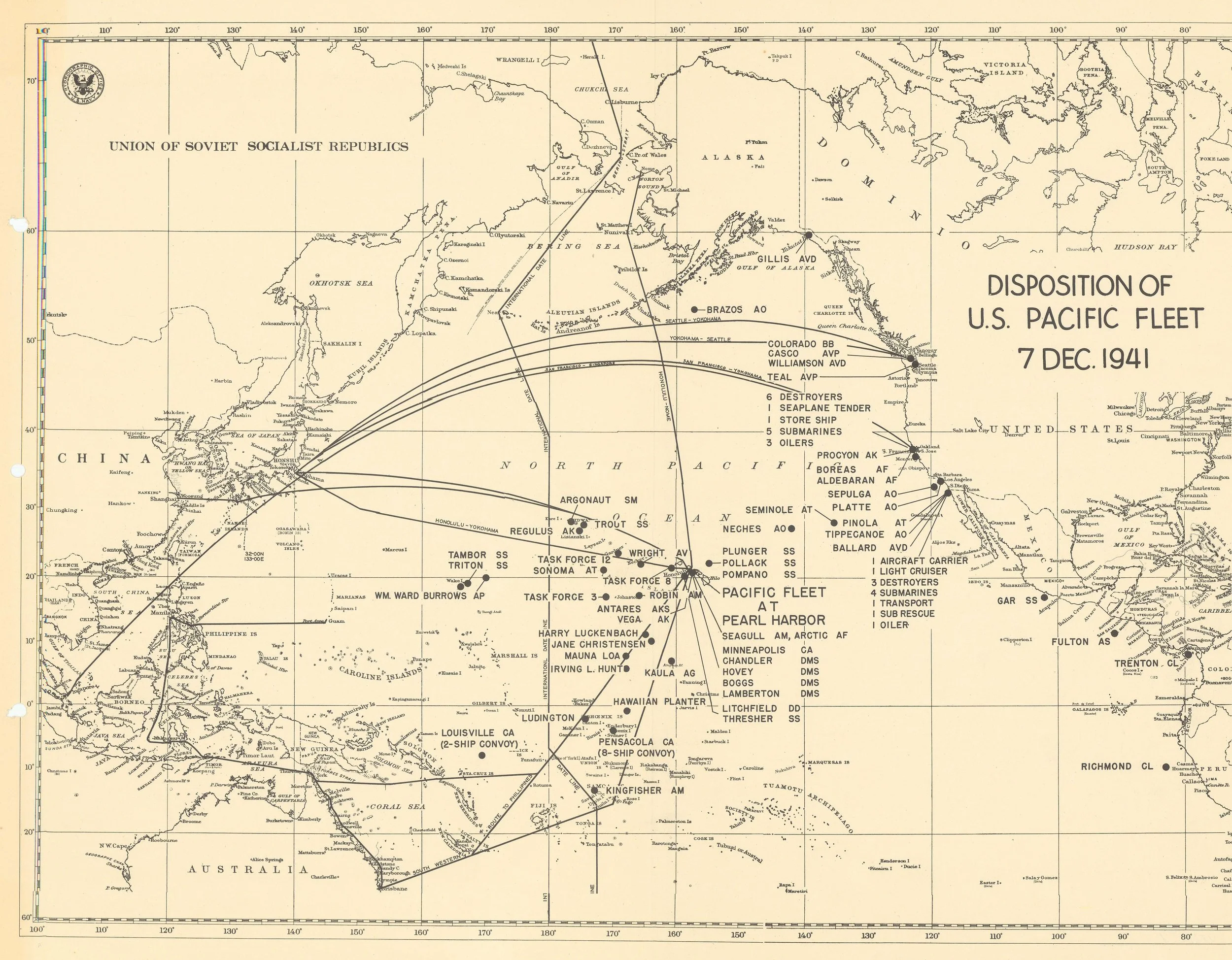

Disposition of the U.S. Pacific Fleet - 7 December 1941

The above map is an excerpt from a report promulgated by the U.S. Navy shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. It shows the location of all the fleet vessels in the Pacific Ocean.

For a complete list of the vessels, as well as a breakdown of each of the Task Forces, please click HERE.

Source: U.S. Navy via the NARA

SNB or SOB?

When Naval Air Station Patuxent was in its infancy and the tower radio was not yet in operation, the skipper of one of the units based there was cleared by green light for flight south in an SNB [a twin-engined Beech]. Five minutes later the tower operator spotted what he thought was the same plane returning and cleared it to land. In reality it was an Army Air Forces AT-11 [the Air Forces’ version of the SNB].

The tower man notified Operations that the Captain had returned, starting a chain reaction which resulted in a telephone call to the skipper's wife, who hurriedly drove the five miles to the station from home. By that time her husband was well south of Norfolk. After diligent search without success she was informed of the true state of affairs. The good lady, unfamiliar with Navy plane designations, frustratedly declared, "But he must be here. The Duty Officer phoned me that the SOB had returned.”

Naval Aviation News - May, 1949

U. S. Naval Air Station Quonset Point, Rhode Island

Quonset’s Fleet Air Mission - circa 1960

A couple of old veterans, one shot five times in combat, are the last of their kind in America’s